Using COVID-19 as a Cover for Binding Regulatory Change: Title IX under Trump

August 14, 2020Archives . Authors . Blog News . Feature . Feature Img . Issue Spotters . Policy/Contributor Blogs . Recent Stories . Student Blogs Article

On August 14, 2020, colleges and universities will be required to comply with what is essentially an overhaul of the Title IX system as it has existed for over the last decade. Title IX has been revolutionary in combating sexual harassment and sexual abuse in schools, on sports teams, and in other educational programs. The commonly referenced “Title IX” is the ninth title in the Education Amendments Act of 1972, a federal civil rights law which states that “[n]o person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Since 1972, blatant pregnancy discrimination has been all but eradicated, the proportion of women earning college and professional degrees has consistently increased, and women have increasingly become college professors. Title IX is now largely seen as protection against sexual assault and harassment, a topic which has garnered much more national attention in recent years. Many, however, do not know where Title IX gets its power. Much of our present-day federal policy is determined by regulatory institutions within the executive branch or by the courts, as the gridlock within Congress leads to very little legislation.

Title IX applies to any education program or activity that receives federal funding. In 1984, the Supreme Court held that Title IX’s protections extended only to a specific program or activity that directly received federal funding. Franklin v. Gwinett County Public Schools opened the door for private individuals to sue an institution requesting relief, usually monetary damages, when they were subject to sex discrimination at that institution. Since then, Title IX cases have fallen largely into three categories: (1) requests for preliminary injunctions of the punishment doled out by the institution, (2) determination of the due process rights the parties have during an investigation, and (3) establishing transgender students’ rights under Title IX.

Starting largely with the Bush Administration, the Office of Civil Rights (“OCR”) began to release non-binding guidances to federal funding recipients regarding their obligations under Title IX. These guidances have given direction on how to apply the case law, define certain relevant terms, deal with potentially conflicting laws, and apply the law to modern issues. These guidances, however, are not binding law because they did not go through the formal rule-making process, which includes a notice and comment period. As a result, these guidances can change as an administration’s priorities change or as the administrations themselves change following an election. This potential for constant change and the guidances’ lack of binding authority lead to confusion on the endurance of recipients’ obligations under Title IX.

The Obama Administration also relied on non-binding guidance to bolster Title IX, releasing guidance addressing issues such as sexual violence, the importance of giving the Title IX coordinator(s) adequate resources, and the inclusion of gender identity in the “on the basis of sex” language in Title IX. The Trump Administration, however, has rescinded many of these guidances and is now using the cover of the COVID-19 pandemic to further restrict Title IX.

Some of the Trump Administration’s first actions revoked parts of Obama’s OCR Guidance. Trump’s OCR’s 2017 Guidance essentially rescinded the 2016 Dear Colleague Letter, which added protection for gender identity, citing the inconsistent application of Title IX to transgender students by the circuit courts as the reason for its rescission. The 2017 Guidance also withdrew the 2011 DCL and the 2014 Questions and Answers. This change rescinded many key provisions in Obama’s OCR guidance including: the extension of the scope of Title IX to off-campus harassment, requiring a response to harassment the school should have known about, requiring a “preponderance of the evidence” standard to be used, not permitting mediation to be used to resolve complaints, and requiring that each school have an independent Title IX coordinator. Trump’s Administration released a Question and Answer in 2017 to expand on the rescission. On May 6, 2020, Trump’s fourth year in office, regulations were finally released following a lengthy rule-making process. It is important to note that, unlike the Obama-era guidance, these regulations are legally binding because they went through the traditional rule-making process.

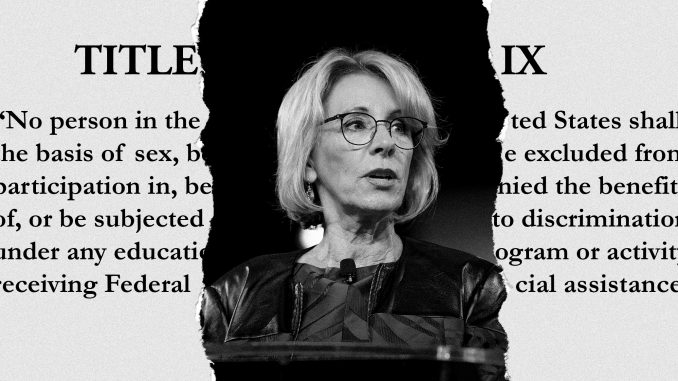

Currently, Education Secretary Betsy Devos and the Department of Education (“DOE”) are using the pandemic as a cover to institute some of the most conservative polices the DOE has introduced in a decade. The definition of sexual harassment has been narrowed to “severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive,” allowing schools to dismiss a variety of complaints that would have been investigated prior to this regulation. Under the new regulation, colleges and universities are not responsible for inappropriate sexual behavior or sexual harassment which occur during study abroad programs or at private, off-campus locations that are not used by officially recognized student groups. According to RAINN (Rape Abuse Incest National Network), only about 8% of sexual assaults would fall within these new parameters. The regulation also requires colleges to provide live hearings for accusations of sexual violence and allows students’ advisers to cross-examine parties and witnesses. Both are potentially traumatic decisions. Ostensibly recognizing this, the regulation allows for ‘informal resolutions’, which must be voluntarily agreed upon by both the victim and the accused. These ‘informal resolutions’, however, cannot include punishment for the accused, putting all the onus on the survivor to adjust their lives to continue attending their institution. Further, Title IX offices are now allowed to use a “clear and convincing evidence” standard, a higher burden of proof that imposes a criminal standard on a civil punishment. Finally, a Title IX coordinator is no longer required to bring a formal complaint against a single respondent after receiving multiple informal complaints of harassment.

Issuing this regulation in the midst of a pandemic, when many colleges and universities are closed or transitioning to virtual learning, is cruel and unnecessary. The regulation also requires colleges to change their policies by August 14th to remain compliant, giving them less than three months after the regulation was released to make the necessary changes. With many institutions currently facing the specter of making unprecedented budget cuts in response to the economic losses of the pandemic, this regulation creates a further complication. The DOE projected more than $300,000,000 in increased costs in the 2020-21 academic year alone. The new regulation requires a minimum of three separate officials – a coordinator, investigator, and a decision maker – instead of the single-investigator model that many universities currently employ. While having multiple officials dedicated to the Title IX office is, in theory, good policy, the swiftness with which this change needs to be made will likely lead to rushed hires of unqualified individuals. The prospect of hiring three additional staff members in a three-month period is unthinkable to many institutions, particularly because institutions typically have at least eight months to implement new departmental rules. Emphasizing the detrimental impact of this new regulation on institutions, Democrats on the House Committee on Education and Labor stated, “Our education system is facing an unprecedented crisis. But instead of focusing on helping students, educators, and schools cope with [COVID-19], Secretary DeVos is eroding protections for students’ safety.”

The policies of the Obama and Bush Administrations shed a light on the pervasiveness of sexual harassment, but these investigations are primarily confined to colleges. Recent events have further propelled discussions about how there are two justice systems in America: one for black people and another for white people. A similar phenomenon exists when adjudicating sexual assault and sexual violence: there is one system for college students and another system for everyone else – the formal criminal justice system. The Trump Administration has responded by implementing more stringent proof thresholds, thus making the college students’ system more like the criminal justice system, and by implementing a needlessly complicated and lengthy regulation. We should be moving in the opposite direction. Fatima Goss Graves, the president and C.E.O. of the National Women’s Law Center, wrote: “We refuse to go back to the days when rape and harassment in schools were ignored and swept under the rug.”

Instead of trying to make the college civil system more like the criminal system, The Department of Education should be requiring comprehensive sex education in primary schools to teach children about consent and boundaries. Title IX trainings are often the most comprehensive sex education students will receive and it is at a time when they are oftentimes 18 years old or older. Proactive measures need to be introduced, including: comprehensive sex education training, information on reporting and remedies, and informing victims of their rights. By starting this education earlier, children will be exposed to the topics of consent, boundaries, and harassment at an early age.

In practice, this regulation provides a baseline for colleges and universities to meet. Many institutions already meet these guidelines by adhering to the substantially more comprehensive Obama-era policies. As long as institutions adjust their policies to comply with the new policies – allowing for cross-examination, hiring three separate officials, offer live hearings – then they are free to continue using the other parts of their current policies which meet a higher standard. However, there will no longer be federal oversight for the areas of a college’s policy that don’t change from what was in place during the Obama Administration. As a result, we will likely see wealthier, better resourced schools maintaining more comprehensive Title IX policies than are required, while other institutions revert to policies that meet the bare minimum requirements. Now, however, all colleges and universities will have the right – and ability – to ignore a complaint when it is convenient. This is exactly the Trump Administration’s intention: to reduce investigations and choose when survivors are heard and when they are not.

About the Author: Kianna Early is a 3L at Cornell Law School. She grew up in Buffalo, NY and has a public policy degree from Cornell University. Kianna is the Managing Editor of Volume 30 of Cornell’s Journal of Law and Public Policy and enjoys writing about pressing policy concerns in the United States.

About the Author: Kianna Early is a 3L at Cornell Law School. She grew up in Buffalo, NY and has a public policy degree from Cornell University. Kianna is the Managing Editor of Volume 30 of Cornell’s Journal of Law and Public Policy and enjoys writing about pressing policy concerns in the United States.

Suggested Citation: Kianna Early, Using COVID-19 as a Cover for Binding Regulatory Change: Title IX under Trump, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (August 14, 2020), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/using-covid-19-as-a-cover-for-binding-regulatory-change-title-ix-under-trump/.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010