Forced Sterilizations — A Discriminatory Reality, Not a Relic of the Past

March 2, 2021Archives . Authors . Blog News . Certified Review . Feature . Feature Img . Issue Spotters . Policy/Contributor Blogs . Recent Stories . Student Blogs ArticleContent warning: Rape, sexual assault.

It has only been six months since a shocking whistleblower allegation regarding forced hysterectomies and medical neglect at an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (“ICE”) detention center in Georgia. Dawn Wooten, a licensed nurse who previously worked at the ICE detention center — the privately-operated Irwin County Detention Center — filed a complaint regarding the numerous hysterectomies performed on Spanish-speaking immigrant women without any prior informed consent. She also expressed concern over the alleged deliberate “lack of medical care, unsafe work practices and absence of adequate protection against COVID-19.” In 2020, these allegations — reproductive organs being forcibly removed without the woman’s consent — almost sounded too inhumane to be true. These allegations, however, have brought to light that forced sterilizations are a remnant of the long legacy of eugenics in the United States and, contrary to popular belief, are not a relic of the past but a harsh reality even today.

Sir Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s half-cousin, coined the term “eugenics” in 1883. The term stemmed from an inaccurate interpretation of Gregor Mendel’s pea pods and Darwin’s theories and stood for the idea that many social ills were perpetuated by rapid reproduction and growth of the “wrong sort of people.” This theory was somehow glorified through the façade of scientific veracity and “eugenics,” the so-called science of “improving humanity through better breeding,” emerged as the solution. The eugenics movement in the United States was a product of the early 1900s and peaked in the 1920s. While the movement itself started losing steam in the 1940s, the practice of sterilizations for eugenics purposes continued well into the 1970s. Between 1907 to 1937, thirty-two U.S. states passed sterilization laws. These states’ sterilization programs were federally funded and government-created eugenics boards in several states were tasked with looking at petitions for sterilizations from government agencies or family members and mandating sterilizations accordingly. As such, almost 70,000 Americans — a lot of them women — were subject to forced sterilizations during the twentieth century.

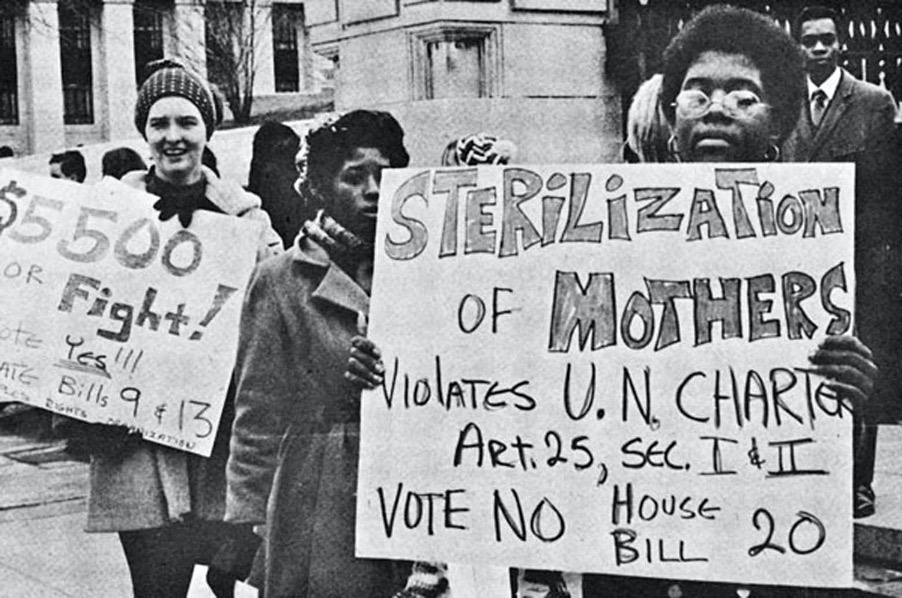

As if the idea of forced sterilizations was not horrifying enough, a clear bias permeated the practice and the entire concept of eugenics. Not surprisingly, those who were considered “unfit” or “different” were usually immigrants, Blacks, Indigenous people, poor whites, and people with disabilities. The eugenics movement became a flagbearer of racism and sexism. Women and people of color were targeted disproportionately, as evidenced by North Carolina’s eugenics board ordering the forced sterilizations of more than 8,000 people, 65% of whom were Black women. In the South, forced hysterectomies on Black women became so prevalent that they were given a euphemism: a “Mississippi appendectomy.”

The eugenics movement found its legal support in the 1927 Supreme Court case of Buck v. Bell, remembered for Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s parting thoughts: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Carrie Buck had been committed to a state mental institution, the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, after giving birth to an illegitimate child who was the product of rape. In 1924, Virginia adopted a statute that authorized the state to sterilize “so-called mental defectives or imbeciles.” Albert Priddy, the physician superintendent at the state mental institution where Buck was committed, decided to test the legal validity of this newly-enacted eugenics law and selected Buck as the subject of the first sterilization. Under the Virginia law, a hearing was required to determine whether the sterilization was necessary. A sham hearing was held for Buck, in which Priddy declared Buck “congenitally and incurably defective.” The Board of Directors then ordered the sterilization, which Buck challenged initially in the Virginia court system, and then in the Supreme Court. In an eight-to-one decision, the Supreme Court upheld the Virginia statute and declared that it was in the state’s interest to have Buck sterilized. This decision, a huge victory for the eugenics movement, essentially legalized forced sterilizations for eugenics-motivated purposes in the United States.

Buck, however, when interviewed by reporters years later, stated that she would have liked to have children and never really understood the nature of the sterilization procedure. Buck’s statement echoes a common feature of most forced sterilization procedures — a lack of information, and subsequently, the lack of informed consent. Either the procedure is administered without the woman’s knowledge, or her right to consent is taken away from her. The documentary No Más Bebés showcased how, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, doctors used coercion tactics to obtain consent from Mexican immigrant women to perform sterilizations on them in a Los Angeles hospital. The doctors threatened these non-English speaking women by withholding treatment or telling them their babies might die in order to force them to sign consent forms. The women only found out later that the barely discernable papers they had signed in a state of disorientation and pain actually resulted in the loss of their reproductive rights. The doctors targeted vulnerable Latina women who woke up after the procedure confused and deprived of their reproductive rights due to coercion and a general lack of information. These instances in the documentary echo the descriptions of alleged forced sterilizations at the ICE detention center in 2020.

In the twenty-first century, most instances of forced sterilizations are illegal — doctors are required to follow established procedures and guidelines and inform patients of their reproductive rights. Additionally, forced sterilizations violate several international human rights standards. Despite these international regulations, the practice still continues, especially in jails, prisons, and detention centers. Between 2006 and 2010, nearly 150 women, the majority of whom were Black and Latina, were sterilized through tubal ligations against their consent in California prisons. Since federal funds could not be used to pay doctors for performing these sterilizations, California used state funds to pay these doctors almost $150,000. In discussing the payments to doctors to perform these sterilizations, one doctor noted that the nearly $150,000 of state funds used to pay the doctors “paled in comparison to ‘what you save in welfare,’” implying that the state would have paid more through its welfare program had these inmates had children after being released from prison. This kind of rationale has persisted, with a Tennessee judge, as recently as 2017, offering repeat offenders “reduced jail time in exchange for sterilization operations.”

Considering this country’s torrid history with eugenics and sterilizations, the recent ICE incident should hardly come as a surprise. The whistleblower allegations attracted widespread outrage, with Representative Ayanna Pressley and Representative Pramila Jayapal calling for a Congressional investigation into these unconstitutional human rights violations. Hopefully those responsible for the atrocities at the detention center will be held accountable. In the meantime, it cannot be emphasized enough that interferences with individuals’ reproductive rights and bodily autonomy are not a thing of the past. They are very much a reality, even today, and disproportionately target the “less fortunate and poorly educated.” Unless we collectively raise awareness to change policies, instigate and mobilize policy makers, and educate on the importance of informed consent, the reproductive freedom that we so desire is a far-fetched possibility in the battle against forced sterilizations.

About the Author: Madhura Banerjee is a 2L at Cornell Law School. She grew up in Kolkata, India and has a law degree from Jindal Global University, India. She is interested in corporate law and intellectual property and eventually hopes to pursue a career in those areas.

Suggested Citation: Madhura Banerjee, Forced Sterilizations — A Discriminatory Reality, Not a Relic of the Past, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter (Mar. 1, 2021), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/forced-sterilizations-a-discriminatory-reality-not-a-relic-of-the-past/.

You may also like

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010