One Person, No Vote: How Gerrymandering Will Steal Our Elections if We Don’t Stop It

October 30, 2020Archives . Authors . Blog News . Certified Review . Feature . Feature Img . Issue Spotters . Note Adaptation . Notes . Policy/Contributor Blogs . Recent Stories . Student Blogs Article(Source)

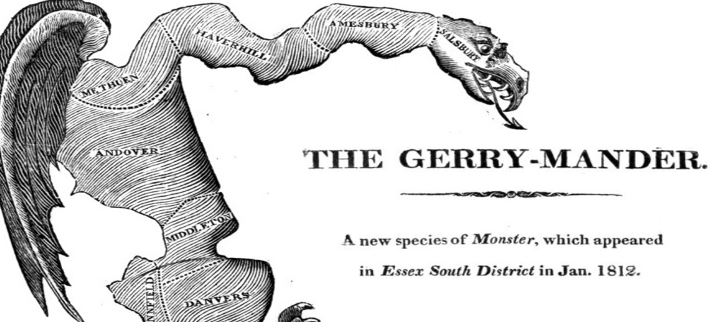

This is an actual, real-life statement made by Representative David Lewis, a Republican member of the North Carolina General Assembly’s redistricting committee. And it wasn’t made at a political fundraiser or at a campaign rally—it was made at an official meeting of the North Carolina state legislature, a body that purports to put the voices of its constituents above its own partisan goals. Even more alarming than the statement itself is the fact that Representative David Lewis and his colleagues were able to do exactly what he proposed, and with the blessing of the U.S. Supreme Court.

You may be thinking that Lewis’s statement is disturbing but that we have more important and urgent things to worry about—after all, we are only days away from the November election, and we need to focus all of our energies on getting our friends and family to turn out to vote. If we can do that, then the changes we hope to see in this country will soon after follow. It’s a simple numbers game, right?

The unfortunate answer is no, and that’s because the landscape of our entire electoral system radically changed after two Supreme Court decisions: Shelby County v. Holder (2013) and Rucho v. Common Cause (2019). We are now about to experience the full and combined gravity of those two decisions for the first time since they became the law of the land, as we near the completion of the decennial Census and prepare to send new population data to state legislators like Representative David Lewis in North Carolina so that they can redraw our voting districts. Federal law requires that states redistrict after each Census to allow them to adjust to the addition or loss of congressional seats and to ensure that districts continue to be proportionate amidst normal fluctuations in population. But this time around, they’ll have very few legal barriers to stop them from redrawing those voting districts in a way that disenfranchises non-white voters.

They will do this through practices called “cracking“ and “packing“. Cracking refers to spreading a constituency of voters—say Democrats or Black voters—thinly across multiple voting districts so that their voice isn’t ever strong enough to constitute a majority in any one district. Packing, conversely, refers to funneling all of those same voters into just a few districts so that their impact is cabined and can’t influence electoral outcomes elsewhere. Both cracking and packing are forms of vote dilution, which refers to the use of redistricting to reduce the strength of a demographic group’s voting power.

Although using these practices to dilute votes based on race is technically illegal, the Shelby County decision made it much easier to do so and evade legal scrutiny, in that it freed nine states (with disturbingly well-documented histories of disenfranchising voters based on race) of the obligation of clearing changes to their election procedure with the United States Attorney General prior to implementing them. Those histories include Arizona creating a literacy test in an effort to disenfranchise 100,000 new Hispanic citizens; Texas embracing a poll tax; and Mississippi adopting the “Grandfather Clause” granting the right to vote only to those whose grandfathers had been eligible to vote before the Civil War.

The kind of federal oversight that Sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act provided before Shelby County was critical to preventing the continued creation of these types of laws, as well as their result, which was to disenfranchise voters based on race. This was especially important given that the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution—Article I, §4, Clause 1—otherwise grants the states the primary authority to regulate the “times, places, and manner” of holding elections. Through this Constitution-given power, states can do things such as require people to register to vote, mandate the polling place at which they can vote, and determine absentee voting eligibility and requirements. In a post-Shelby County world, all of this happens with very little federal oversight.

As if to add insult to injury, six years after Shelby County, the Supreme Court decided Rucho and held that it would not intervene to stop the kind of partisan gerrymandering that Representative Lewis spearheaded in North Carolina. Given the large overlap between Democratic voters and non-white voters, it is immensely difficult to distinguish these partisan gerrymanders—which are (alarmingly) permissible—from racial gerrymanders—which are not.

So, where does this leave us, and what do we do about it? It leaves us inches away from a world where the David Lewis’s of your state have the power to overshadow the voices of the people they are supposed to represent and to engineer elections to meet their own partisan aims. It leaves us inches away from a world where your vote may not technically be denied, but it could be diluted, and the law will not be there to protect you. And it leaves us inches away from a world where the “one person, one vote” principle that the Court announced in Reynolds v. Sims and Baker v. Carr becomes nothing more than a phrase to describe the kind of representative democracy that we hoped to call our own but never fought hard enough to actually possess.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can take the power to re-draw our voting districts away from partisan legislators who want to suppress the will of the people and we can transfer that power to the place it belongs: with the people directly. We can do this by creating independent commissions of citizens that are specifically engineered to be non-partisan and are required to use clear, prioritized criteria to guide their work and then communicate transparently about why they are drawing maps the way that they are. We can live in a world where “one person, one vote” becomes not just a hope for a future, but a descriptor of the present. But we can only live there if we let the people choose their representatives, as they were always intended to.

Check out more about this topic in Marisa’s Note—The Independent Citizen Commission: Our Best Chance at Ending Racial Gerrymandering and Restoring the Promise of the Voting Rights Act of 1965—in Volume 30.1 of Cornell’s Journal of Law and Public Policy, which will be published in early November.

About the Author: Marisa O’Gara is a third-year student at Cornell Law School. She is a member of the Capital Punishment Clinic and volunteers regularly for the Election Protection Hotline and the National Voter Assistance Hotline. Before law school, Marisa was Campaign Manager for current Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza. She led a campaign team to a primary victory against a sitting City Council President and a general election victory against former Mayor and political juggernaut Vincent “Buddy” Cianci. Following a successful campaign, Marisa joined Mayor Elorza’s administration and served as his Deputy Chief of Staff for three and a half years. Marisa also worked on U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s re-election campaign and Rhode Island’s successful campaign for marriage equality. She holds a B.A. in English and a B.A. in French from the University of Rhode Island.

About the Author: Marisa O’Gara is a third-year student at Cornell Law School. She is a member of the Capital Punishment Clinic and volunteers regularly for the Election Protection Hotline and the National Voter Assistance Hotline. Before law school, Marisa was Campaign Manager for current Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza. She led a campaign team to a primary victory against a sitting City Council President and a general election victory against former Mayor and political juggernaut Vincent “Buddy” Cianci. Following a successful campaign, Marisa joined Mayor Elorza’s administration and served as his Deputy Chief of Staff for three and a half years. Marisa also worked on U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s re-election campaign and Rhode Island’s successful campaign for marriage equality. She holds a B.A. in English and a B.A. in French from the University of Rhode Island.

Suggested Citation: Marisa O’Gara, One Person, No Vote: How Gerrymandering Will Steal Our Elections if We Don’t Stop It, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y: The Issue Spotter (Oct. 30, 2020), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/one-person-no-vote-how-gerrymandering-will-steal-our-elections-if-we-dont-stop-it/.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010