Native Nations & Rural America: An Unlikely Partnership?

October 23, 2020Archives . Authors . Blog News . Certified Review . Feature . Feature Img . Issue Spotters . Policy/Contributor Blogs . Recent Stories . Student Blogs ArticleIntroduction

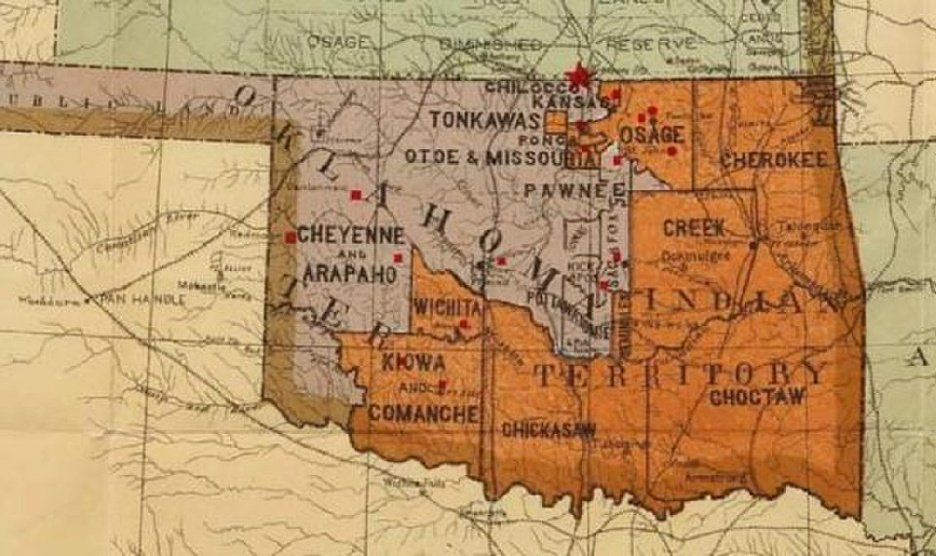

In the wake of McGirt v. Oklahoma, Tribes across America celebrate the Supreme Court’s reaffirmation of tribal sovereignty and self-governance. In the landmark case, the Court held that the Muscogee Creek reservation had not been disestablished and that criminal jurisdiction remained with the Tribe and the federal government – not the state. This cause for celebration brings with it new economic pressures for Oklahoma Tribes. With criminal jurisdiction, a Tribe must have adequate infrastructure including courts, jails, employees for both, and additional resources related to criminal justice systems.

The Court’s decision restored criminal jurisdiction to the Tribe for much of Eastern Oklahoma. The reservation spans over three million acres, and includes the state’s second largest city, Tulsa. Although criminal jurisdiction is limited by the Major Crimes Act, nearly 300,000 Native Americans live within the reservation. Cases involving Native American perpetrators of a crime on the reservation are now directed to the Tribe’s one district court, Okmulgee, where the court and the tribal services are located, is a forty-five minute drive from Tulsa, and an even further drive for individuals from towns at the edge of the reservation. For successful application, the McGirt ruling demands funding and infrastructure that the Tribes currently lack.

Oklahoma’s Governor, Kevin Stitt, took offense to the McGirt ruling and has since tried to undermine the ruling by calling on Congress to interfere and by creating a commission on cooperative sovereignty lacking tribal representatives. Meanwhile, rural Oklahoma’s economic struggles persist. Within the past twenty years, major employers of skilled workers, including hospitals and auto and textile manufacturing companies, have vanished from the state. The pandemic has created additional economic strains and renewed calls for change. An unlikely partnership between rural Oklahoman communities and Oklahoma Tribes might be the solution.

The State

Oklahoma ranks among the ten poorest states in the United States. The 2018 federal poverty line marks the threshold for a family of four at $25,465 and a single parent family with one child at $17,308. Because these numbers do not account for regional differences, the National Center for Children in Poverty (NCCP) notes that the level of income families realistically need to make ends meet is actually two times the federal threshold. Oklahoma’s median household income in 2018 averaged a little more than $54,000. According to the federal threshold and NCCP, the average Oklahoman is barely above the “actual” poverty line.

With a poverty rate of 15.8% and unemployment rate of 4.5%, understanding the cause of an economic gap on its face is challenging. To better understand the problem, the state’s history is the best place to start. Food insecurity, poverty, and drought have existed in Oklahoma since before statehood. Andrew Jackson forcibly removed Indigenous Nations from their Eastern homelands and settlers traveled westward to escape overcrowding in east coast cities. Then, the Great Depression struck. At that time, half a million residents abandoned Oklahoma. Those that were left continued to press on in building infrastructure and farmlands after the markets recovered. Still today, one in six Oklahomans live in poverty. This is likely a result of traditional causes of poverty, such as underemployment, low wage work, and mass incarceration. In addition to these factors, Oklahoma suffers from isolation and a lack of amenities. With little to attract new residents and tourists, Oklahomans must look for new yet near opportunities to bridge the economic gap.

The Tribe

Although many Oklahomans have struggled to break the generational chain of poverty, the Native American Nations have made economic strides. For example, the Muscogee Creek Nation’s 2020 annual budget totaled over $350 million and the Cherokee Nation’s was $1.16 billion. Tribes are sovereign nations and, like countries, must engage in nation building. The Tribes in Oklahoma have built casinos, restaurants, hotels, museums and more. Attorneys for the Creek Nation in McGirt v. Oklahoma cited the Tribe’s economic successes in their argument for maintaining reservation jurisdiction. Until recently, these economic strides were enough.

Three months after McGirt, tribal government departments in Oklahoma are still seeking strategies to develop infrastructure and funding. Despite the two-year gap between the granting of certiorari of Sharp v. Murphy, McGirt’s predecessor, and the release of Justice Gorsuch’s McGirt decision, Tribes across Oklahoma are not prepared to handle the workload. The need for increased staffing in child welfare and adult protective services departments, substantial construction of additional courthouses, and dramatic budget increases across all departments are just a few of many concerns at the forefront of the Creek Nation’s government.

There are thirty-nine sovereign Native Nations in Oklahoma, and many of those seek to replicate McGirt’s results for their own communities. Because treaty language used with each of these Tribes are similar in nature, it is likely that most of these Nations will succeed. With tribal jurisdiction restored to more Oklahoma reservations, the need for further infrastructure and funding only increases.

A Mutually Beneficial Relationship

Thus, an unlikely marriage presents itself as a potential solution:Tribal nation building hand-in-hand with small town, rural Oklahoma development. McGirt’s award of tribal sovereignty reignited a need for tribal nation building. By creating more tribal infrastructure and businesses, both tribal and non-tribal communities in Oklahoma will grow. Because of Oklahoma’s allotment history, many non-Native families live within the reservation boundaries, and they too will benefit from tribal development.

Given these economic development endeavors, the Tribes need capital. Although Tribes generate a substantial amount of income each year, the help of outside investors must be employed. In 2017, Congress enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) which identified “opportunity zones” across the U.S. Opportunity zones are low income census tracts identified with the goal of bringing capital into economically distressed areas. Of the 8,700 opportunity zones identified by the Act, more than ninety of those zones are on Oklahoma tribal land. Tribal governments with land identified as opportunity zones are excluded from pooling investments for development projects through the TCJA because the Indian Reorganization Act controls how tribes create corporations. Although Tribes were excluded from participating in the opportunity zones, Tribes may still use these highlighted opportunity zones to attract investors and create state-chartered corporations.

Finally, both the Tribes and the state might benefit from either the state or the federal government forming a program similar to the one created in the TCJA. Several years have passed since TCJA’s enactment, giving the state an opportunity to evaluate its successes and shortfalls. This information could provide a framework for the state to apply the TCJA model to a similar program involving Tribes through state-chartered corporations. Under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act, tribes are not subject to federal income tax and may create corporations, making available the same advantages that TCJA did for non-tribal lands. Another avenue proposed by the Native American Finance Officers Association (NAFOA) is to simply extend the TCJA to include Native American Nations with land in opportunity zones. An organized initiative with the backing of the federal government may be better suited to draw outside investors into Indian Country. This program may also be implemented in other states, considering that more than 200 additional opportunity zones exist throughout Indian Country.

Tribal Sovereignty & Outside Investors

The benefit of outside investors will come at a cost. Like states and the federal government, Tribes inherently possess sovereign immunity. Without a waiver of immunity, investors bear the brunt of economic risk in joint endeavors, which is one reason why outside investors hesitate to partner with Native Nations. If Tribes are to rise to the occasion, they must strategically waive their immunity to bring economic growth to Tribes and their surrounding communities. In doing so, tribes will be much more attractive business partners. Additionally, if investors fund tribal-incorporated business endeavors, they will gain benefits much like the ones promised in the TCJA. For example, Tribes and their tribal-incorporated businesses do not pay federal capital gains taxes.

Conclusion

Oklahomans and Native Nations share a similar history of exhibiting resilience during trying times. In a time when all communities are facing unprecedented challenges, partnership and collaboration are key. The issues faced by the state and Oklahoma Tribes are not unique to those sovereigns. The state’s economic strains are similar to those across rural America, and Oklahoma Tribes are confronting questions of economic development like many Tribes throughout Indian Country. By joining efforts, rural Oklahoma communities and Native Nations can serve as a model to other areas of the United States.

About the Author: Emily Harwell is a Mvskoke (Creek) tribal member and a 2L at Cornell Law School. Emily is the President of Cornell’s Native American Law Student Association. This summer, she clerked at the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) where she worked on Native American voting rights litigation. Emily is interested in research topics related to the intersection of Federal Indian Law and Civil Procedure.

About the Author: Emily Harwell is a Mvskoke (Creek) tribal member and a 2L at Cornell Law School. Emily is the President of Cornell’s Native American Law Student Association. This summer, she clerked at the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) where she worked on Native American voting rights litigation. Emily is interested in research topics related to the intersection of Federal Indian Law and Civil Procedure.

Suggested Citation: Emily Harwell, Native Nations & Rural America: An Unlikely Partnership?, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y: The Issue Spotter (Oct. 23, 2020), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/native-nations-rural-america-an-unlikely-partnership/.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010