The Hoax and the Home: Assessing the Legal Remedies Against Swatting

November 8, 2018Archives . Authors . Blog News . Certified Review . Feature . Feature Img . Recent Stories . Student Blogs ArticleIn 2008, the FBI published an online report about a new phenomenon called “swatting,” in which one individual (the “swatter”) calls 911 and falsely reports an emergency with the intention of leading law enforcement, typically a SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) team, to the location of a targeted individual. Although the particular emergency described by the caller can vary, most cases involve the caller reporting they are participating in or witnessing a home invasion, active shooter, or hostage situation. The seriousness of the described situation often prompts a rapid response from heavily-armed law enforcement officials. However, given that the targeted individual knows nothing about the hoax taking place, law enforcement often arrives on the scene only to realize that the deranged kidnapper or murderer described on the emergency call is in fact an innocent victim of swatting.

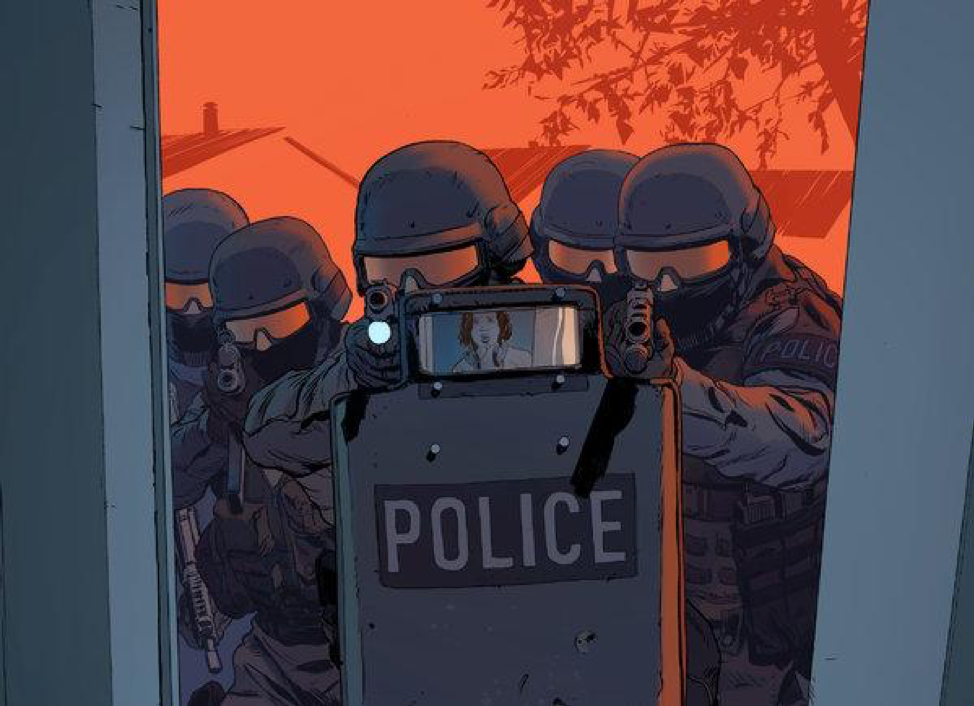

A 2017 swatting case illustrates how the offense is more serious than a mere prank call. On December 28, 2017, Tyler Barriss called the Wichita police and pretended that he had murdered his father and was holding hostages in his home. The police believed his threats were credible and dispatched officers to the address Barriss provided. In actuality, Barriss made the call from his home in California and allegedly received the address and swatting request from an online gamer, Casey Viner, seeking retaliation against another gamer, Shane Gaskill, whom he had played against in an online video game match. The problem, besides the swatting itself, was that the address belonged to 28-year-old Andrew Finch, not Gaskill. Finch, who was not involved in the video game dispute and did not know Viner, Gaskill or Barriss, opened his front door to a swarm of police officers with their weapons pointed at him. Although many swatting situations end with the police realizing that the emergency was a hoax, Barriss’s swatting call led to a single gunshot from an officer’s weapon to Finch’s chest, killing him.

Swatting poses a particularly difficult challenge for law enforcement due to the ability of the callers to mask their identity and location. Swatters can call non-emergency lines and then ask to be transferred. Swatters can also use voiceover internet protocol (VoIP) numbers that appear to be in the same area code as their intended victims. Moreover, numerous websites and phone applications offer spoofing services, which enable malicious callers to hide their actual location, change their voice, and insert background noise. In addition, swatters can create anonymous profiles for messaging applications and online phone services like Skype to send hoax text messages and make emergency calls.

Tracking the origin of the swatting phone calls requires a significant amount of police resources and time. In order to ascertain the identity of an anonymous caller, law enforcement can subpoena VoIP providers to provide the phone numbers called by the swatter, logs detailing when each call was made, and the email addresses and websites used to sign up for the VoIP services. Such investigations can require thousands of hours, as was the case in a 2014 swatting investigation by a detective sergeant outside of Atlanta.

In response to the swatting death of Andrew Finch, Kansas Governor Jeff Colyer signed into law the Andrew Finch Act on April 12, 2018. Under the law, “anyone who makes a false alarm or swatting call that results in death or extreme injury would face a level one felony, which carries a prison sentence between 10 and 41 years, depending on criminal history.” The purpose of the law is twofold: it memorializes the tragic death of Finch and reflects the state’s explicit recognition that swatting carries serious consequences. It is unclear, however, how effective the law will be in deterring individuals from engaging in swatting. The plethora of spoofing services available to potential swatters is likely to give them the confidence that police will not be able to track them down. Despite the passage of the Finch Act and the widespread attention that his death brought to the crime of swatting, Kansas police have already investigated two swatting incidents in 2018.

On the federal level, prosecutors can find success in charging swatters under 18 U.S.C. § 2292. Under subsection (a) of the statute, a civil penalty of up to $5,000 is imposed on anyone who “imparts or conveys or causes to be imparted or conveyed false information, knowing the information to be false, concerning an attempt or alleged attempt being made or to be made, to do any act that would be a crime prohibited by this chapter or by chapter 111 of this title.” Subsection (b) adds the potential penalty of up to 5 years of imprisonment if an individual “knowingly, intentionally, maliciously, or with reckless disregard for the safety of human life, imparts or conveys or causes to be imparted or conveyed false information, knowing the information to be false, concerning an attempt or alleged attempt to do any act which would be a crime prohibited by this chapter or by chapter 111 of this title.”

Almost every swatting would satisfy the mens rea elements in both subsections of § 2292. Any swatter would meet the mens rea element in subsection (a); because the callers fabricated the emergency situation, they must know the information they are conveying is false. Moreover, a swatter would satisfy the mens rea component in subsection (b), which requires that the individual acted “knowingly, intentionally, maliciously, or with reckless disregard for the safety of human life.” Defendants could argue that they did not act maliciously because they merely engaged in swatting as a prank. However, the knowing and intentional elements can be proven easily for the same reasons used to satisfy the mens rea element in subsection (a). To prove that a swatter acted with reckless disregard for the safety of human life, the government would need to convince a jury that the human life in question is the targeted resident or the officers dispatched to the scene. By choosing to call emergency services and describing a dire situation where someone has already died or will die soon, an individual making a swatting call accepts the possibility that the arrival of a heavily-armed SWAT team on high alert will lead to someone being injured.

Although Barriss is currently being prosecuted on state crimes, the government would likely succeed in prosecuting him under § 2292. He conveyed to law enforcement information about a shooting and hostage situation while knowing that such information was false. Federal prosecutors have already succeeded in charging a swatting perpetrator under § 2292. In 2015, Matthew Tollis of Wethersfield, Connecticut pled guilty to conspiring to engage in the malicious conveying of false information, namely a bomb threat hoax. Tollis was sentenced to an imprisonment term of 12 months and one day. If prosecuted under § 2292, Barriss could be sentenced to a similar imprisonment term, or one up to five years.

The government can also charge a swatter for transmitting threats via interstate communications under 18 U.S.C. § 875. Subsection (c) of the statute, which applies to “[w]hoever transmits in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another,” would apply to instances of swatting where the malicious caller describes a hostage, kidnapping or murder situation. Federal prosecutors in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania succeeded in charging a perpetrator of swatting under § 875. 20-year-old Michael Anthony Nohl of Oaks, Pennsylvania pled guilty under the statute after engaging in a phone call in which he threatened to kidnap and murder a law enforcement officer and the officer’s family. As swatters explore new ways to mask their location and make the false emergency phone calls from states far away from the states where their targets reside, federal prosecutors can look to § 875 as an appropriate law for the offense. Barriss would likely be found guilty under § 875(c) given that he called the Kansas police from his location in California, thereby engaging in interstate communication. Under subsection (c) of the statute, Barriss would face an imprisonment term of up to five years.

Beyond the existing statutes that could apply to swatting cases, federal legislation that explicitly addresses swatting has been recently proposed. On June 5, 2018, Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY) introduced to the House of Representatives the “Anti-Swatting Act of 2018.” Through the bill, Engel sought to amend § 227(e)(5) of the Communications Act of 1934 to add a subsection entitled “Enhanced Penalties for Violation with Intent to Trigger Emergency Response.” As a criminal penalty, Engel proposed an imprisonment term of up to five years if found guilty under § 227(e) and an imprisonment term of up to 20 years if serious bodily injury results. In addition to creating a criminal penalty for falsifying one’s caller ID information to mislead law enforcement, Engel’s bill would force swatters to reimburse the emergency services who dispatch the law enforcement officials in response to the fake emergency.

Congress would be wise to pass the Anti-Swatting Act of 2018 in order to more effectively prosecute cases of swatting and ensure that law enforcement is not deterred from acting on emergency calls. The provision of the bill that imposes criminal penalties appropriately reflects the need to punish individuals who intentionally hide their identity in order to deceive law enforcement about a serious emergency situation. In particular, the subsection of the bill that increases the imprisonment term if serious bodily injury results from the swatting appropriately recognizes that these malicious phone calls can have consequences more serious than the mere waste of police resources and time. However, the bill’s reimbursement provision also addresses the reality that responding to hoax emergencies can cost up to $100,000. Requiring individuals who engage in swatting to pay reimbursements would allow emergency response teams to continue to respond to emergency calls, without any concern about the costs, despite the possibility that the calls are in fact swatting attempts.

While Engel’s proposed legislation and existing statutes may appropriately apply to swatting, non-legislative measures focused on sharpening law enforcement responses can more effectively prevent swatting attempts. Swatting inherently relies on the emergency dispatcher believing the fake emergency is credible. Addressing swatting therefore merits considering how the police can better determine the veracity of the caller’s claim. If police can better distinguish the credible emergency calls from the swatting attempts, there is a lower likelihood that police resources will be misused and that another innocent shooting like that of Andrew Finch will occur. For example, increasing the sharing of technological resources from federal law enforcement with state and local law enforcement would enable the latter to more effectively determine the identity and location of individuals attempting to falsely report emergency situations. In addition, emergency dispatchers and law enforcement should be trained to observe certain indicators that likely point to the phone call or message being a hoax. In 2015, the New Jersey Cybersecurity & Communications Integration Cell released a report entitled, “Swatting: Mitigation Strategies and Reporting Procedures.” The report notes that a phone call may be a swatting attempt if the incoming telephone number is spoofed or blocked, which would appear as all zeros or nines. The report also includes the indicator that if only one phone call is made to an emergency line to report an active shooter or other ongoing massive emergency situation, it is likely that the call is part of a swatting attempt since such an emergency would likely prompt multiple calls to dispatch from witnesses or victims.

Although the shooting of Andrew Finch was the first known death as a result of a swatting, legislators and law enforcement must recognize that future possibilities of swatting may lead to fatal consequences. Passing legislation that recognizes swatting as a federal offense is one way to deter individuals from facing multiple years of imprisonment for misleading law enforcement about a fake emergency situation when there may be a real emergency taking place elsewhere. Moreover, while Barriss’s swatting targeted a home, prior swatting incidents have involved high schools, universities, and businesses, which have led to evacuations and disruptions. The seriousness of the crime of swatting may increase as technology and online services that allow perpetrators to keep their identity and location anonymous become more widely available. Improving current investigative and prosecutorial approaches to swatting will better ensure that Finch’s death is the first and only fatality that results from the offense.

Suggested citation: Ferdinand G. Suba Jr., The Hoax and the Home: Assessing the Legal Remedies Against Swatting, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (Nov. 8, 2018), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/the-hoax-and-the-home-assessing-the-legal-remedies-against-swatting/.

You may also like

- November 2024

- October 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010