To the 117th Congress: Pass the FAIR Act

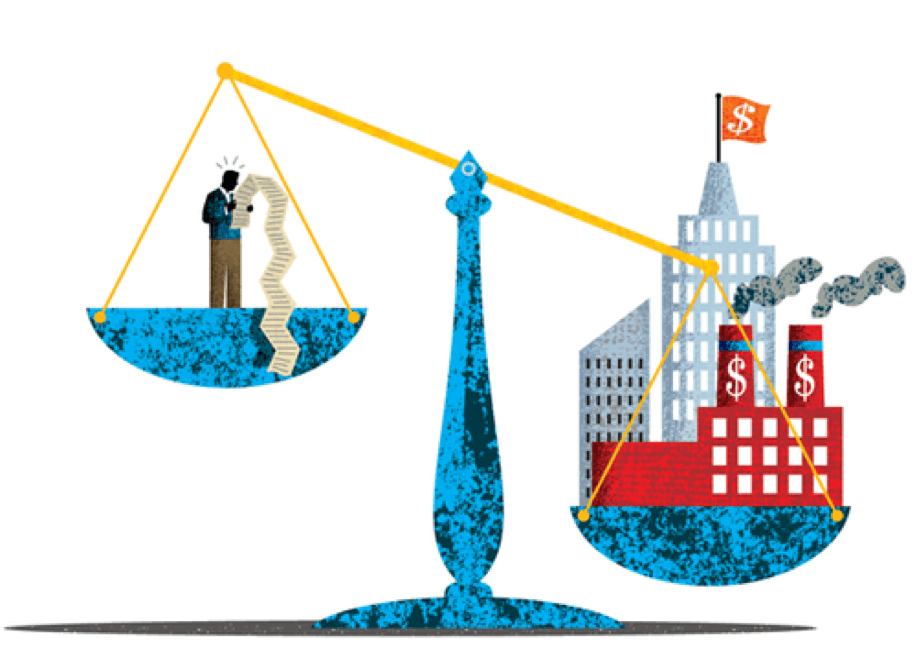

May 3, 2021Authors . Blog News . Certified Review . Feature . Issue Spotters . Recent Stories . Student Blogs ArticleThe right to a jury trial in civil actions, preserved by the Seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution, is quietly being eviscerated. As arbitration provisions have become fixtures within standard-form employment and consumer contracts, millions of individuals may no longer utilize courts to press a variety of civil actions, including medical malpractice, sexual harassment, and discrimination suits. Those individuals are forced to present their disputes before private arbitrators in relatively informal proceedings: arbitrators need not adhere to any rules of evidence and, unlike judges, they do not need to articulate the reasoning behind their awards.

Mandatory arbitration harms employees and consumers. According to Alexander Colvin, a professor of dispute resolution and dean of the Cornell University ILR School, arbitration tends to suppress employment-related claims because claimants are less likely to succeed in arbitration than they are in court and, when they do succeed, the awards are typically smaller than they are in court. Statistics suggest a similar plight for consumer-claimants. For example, according to a New York Times study, Verizon, which had more than 125 million customers as of 2015, faced only sixty-five consumer arbitrations between 2010 and 2014. Moreover, many arbitration provisions in consumer contracts contain class action waivers, which effectively bar consumers from pursuing claims that are not economically worth pursuing on an individual basis.

Mandatory arbitration has proliferated to such an extent due to the Supreme Court’s modern construction of the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”). Passed in 1925, the FAA states that arbitration provisions in contracts “evidencing a transaction involving commerce . . . shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.”

The legislators who passed the FAA did not imagine the law would affect a wide range of cases. Law professor Amalia Kessler attributes the FAA’s enactment to the efforts of Progressive Era lawyers who sought “to develop a set of rules and policies for preventing unnecessary litigation.” Such efforts were made following the recognition that American society’s significant growth during the early twentieth century would create the need for new procedural mechanisms that would allow more individuals to seek redress for legal harms done to them. David Schwartz, a professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School, states that the FAA was viewed as increasing courts’ docket capacity by moving commercial disputes—disputes between merchants—to the realm of arbitration. Indeed, that arbitration was a suitable mode of settling merchant disputes over factual questions including “quantity, quality, time of delivery, compliance with terms of payment, excuses for non-performance, and the like.” Schwartz notes that additional contemporary commentary on the FAA “treats the [Act] as though no constituencies other than the business community—and business lawyers—would be affected.”

The Supreme Court’s modern FAA doctrine strays far from that quaint vision of the Act’s purpose. During the 1980s, the Supreme Court departed from a restrained construction of the FAA and began to articulate a federal policy actually favoring arbitration, even in the context of statutory claims. In Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Mitsubishi brought an action against Soler in federal district court and moved to compel arbitration pursuant to an arbitration provision contained in the sales agreement between the two parties. Soler raised a counterclaim against Mitsubishi under the Sherman Act, alleging that Mitsubishi and another party “conspired to divide markets in restraint of trade.” On appeal, Soler argued that, as a matter of law, courts could not compel arbitration of statutory claims unless the party furthering the statutory claims expressly agreed to arbitrate those claims. The Court rejected that argument, maintaining that “so long as the prospective litigant effectively may vindicate its statutory cause of action in the arbitral forum, the statute will continue to serve both its remedial and deterrent function.” Since Mitsubishi Motors, the Court has gone on to uphold arbitration provisions in customer agreements and employment contracts. The Court has also held that bilateral action is a fundamental attribute of arbitration, effectively giving companies free rein to abuse class action waivers.

The 116th Congress made some effort to halt the proliferation of mandatory arbitration. In February 2019, Representative Hank Johnson introduced the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal (“FAIR”) Act. The FAIR Act prohibits all pre-dispute arbitration agreements with respect to employment, antitrust, consumer, and civil rights disputes, including those argued by classes. While the House of Representatives passed the FAIR Act in September 2019 by a vote of 225-186, an identical bill died in the Senate Judiciary Committee, and no further action was taken by either chamber. Fortunately, however, Representative Johnson re-introduced the FAIR Act on February 11, 2021. “Consumers, workers, and small business people shouldn’t need a law degree to be able to go about their daily lives without giving up their constitutional rights,” said Representative Johnson in announcing the re-introduction of the Act. Senator Blumenthal also re-introduced a substantially identical bill in February.

The FAIR Act would restore the state of arbitration to what the FAA’s enactors originally had in mind. No longer would plaintiffs be forced to arbitrate statutory claims rather than bring them in court. At the same time, disputes between equally powerful business actors could still be arbitrated. Indeed, the Act defines “consumer disputes” as those between sellers of goods or services and individuals seeking damages for personal, family, or household purposes, leaving business actors to arbitrate their own disagreements.

The 117th Congress should pass the FAIR Act to prevent the harm wrought by forced arbitration. Some might charge that the FAIR Act is more stringent than necessary because it seeks to outright prohibit pre-dispute arbitration agreements in certain contexts rather than mitigate their harmful effects by, for example, requiring arbitral processes to be more transparent or claimant-friendly. Indeed, at least one academic, Judith Resnik, intimates that mass arbitration would be constitutional if it was more egalitarian and more transparent. Conceivably, then, a law merely prohibiting class-action waivers and requiring arbitrators to articulate the reasoning behind their awards would suffice to mitigate the damage.

In reality, the FAIR Act’s wide breadth is necessary because the proliferation of such agreements threatens precious social capital. Courts play a critical role in fostering social capital. Social capital encompasses the appreciation for civil society—the peaceful, broad-scale interaction of individuals congregating in community nexus points. A healthy civil society indicates high levels of cooperation and reciprocation among its participants. Courts encourage high levels of cooperation and reciprocation by representing instruments of the rule of law. In other words, when citizens interact with courts, they are reminded of the great social contract to which we all adhere on a daily basis—if you follow the law, then I’ll follow the law, and vice versa. However, when individuals are denied their day in court, their trust in the rule of law erodes, social capital diminishes, and civil society becomes less civil.

In an era marked by social and political turbulence, the FAIR Act could play a vital role in restoring faith in civil society and the government institutions that support it. With that renewed faith, perhaps individuals would even see a greater value in public works projects, such as, for example, modernizing infrastructure and embracing green technologies. Therefore, the 117th Congress must seize the new opportunity to enact the FAIR Act.

About the Author: Nicholas Swan is a J.D. candidate in the class of 2022 at Cornell Law School. He graduated from Cornell University in 2019.

Suggested Citation: Nicholas Swan, To the 117th Congress: Revive the FAIR Act, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y: The Issue Spotter (May 3 2021), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/to-the-117th-congress-pass-the-fair-act.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010