School Book Bans: The Fight for Students’ Right to Read

October 28, 2023Feature Article

1,557 books. 33 states. 153 districts.

The 2022-23 school year saw record-breaking numbers of book bans in schools and libraries across the country. PEN America, a nonprofit committed to promoting free expression, recorded 3,362 instances of book bans in the 22-23 school year, a 33 percent increase from the year before. These books, mostly young adult fiction novels, deal with issues of health and well-being, contain sexual experiences between characters, and/or contain non-white or LGBTQ+ characters.

The recent surge in book bans has been fueled by state legislation. Missouri passed a law that bans depictions of “sexually explicit” material. In Tennessee, it’s now a felony for book publishers, distributors, or sellers to provide any matter deemed to be “obscene” to K-12 public schools. A Texas law requires that booksellers rate books based on their sexual references or they won’t be able to sell to public schools.

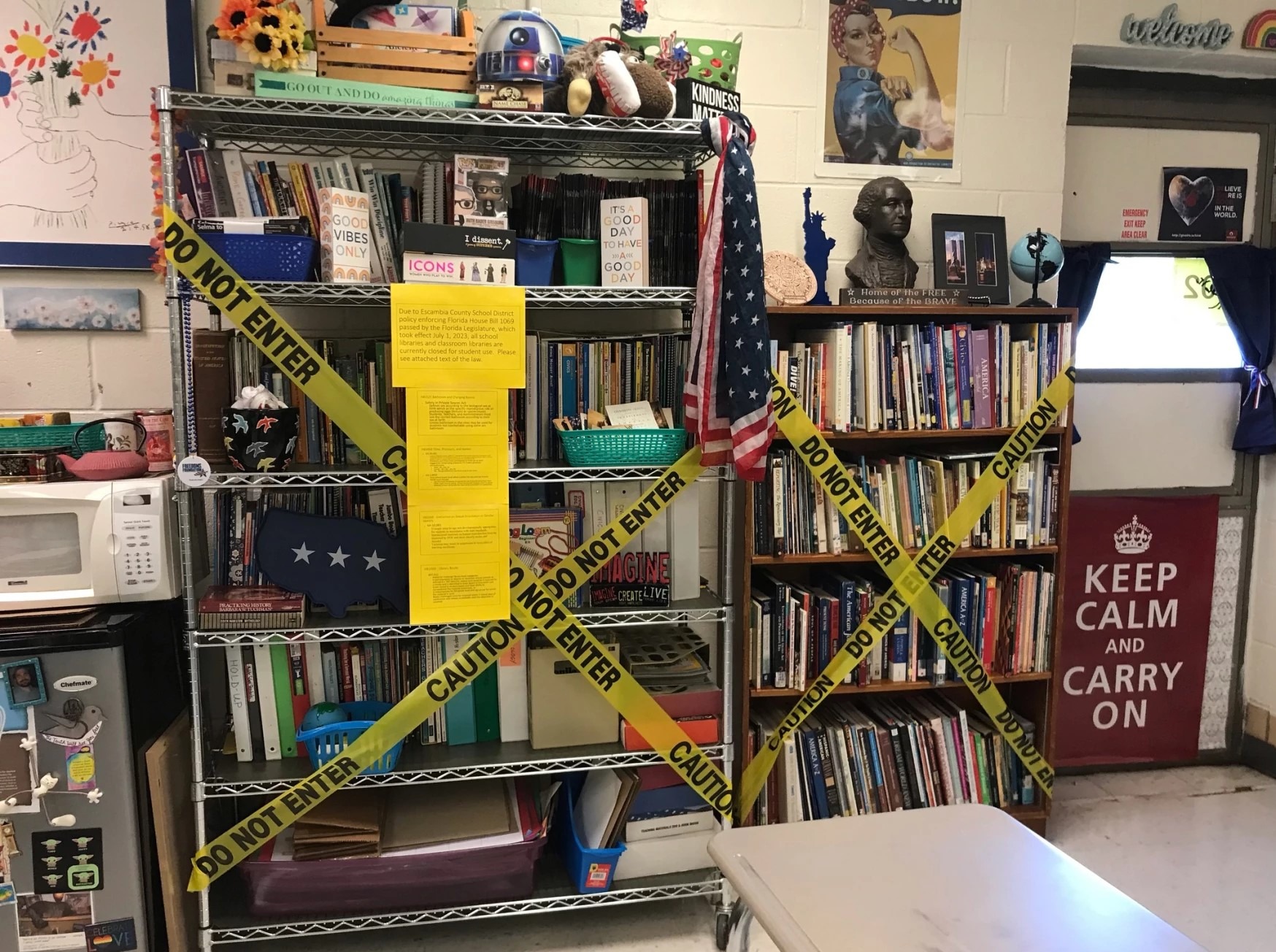

In Florida, a series of recently passed laws have contributed to censorship in schools across the state. Florida House Bill 1467 requires that an individual with an educational media specialist certificate review all public school books for “pornography” or “race-based teachings.” These individuals must also complete an online training program created by the Florida Department of Education for selecting appropriate materials. The bill also gives members of the public increased control over which books are allowed in classrooms and school libraries. House Bill 1557, known colloquially as Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” Bill, has bolstered challenges to books containing LGBTQ+ content and characters by members of the public. Another new law, HB 1069, requires that any challenged book be removed pending resolution of the objection, and school boards must discontinue the use of any material that the board does not allow a parent to read aloud. These laws have made school board meetings a political battleground for the discussion of what can and should be taught in schools. Politically Conservative groups like Moms for Liberty read excerpts of books at board meetings to remove books with any mention of sex. Some of the books banned for “sexual conduct” are books frequently used in school curriculums both in the state of Florida and across the United States, including “The Color Purple,” “Catch-22,” “Brave New World,” and “The Kite Runner.”

In Escambia County, Florida, more than 160 books have been banned for “inappropriate content.” On March 22, 2023, Michelle White, Coordinator of Library Services for Escambia County School District, turned in her letter of resignation after serving the Escambia County School District for 12 years. White said:

“It was not easy. But I couldn’t just go to another district in the state, I really didn’t even want to be in the South. I love the South. Again—I’m from the South. But this was a pattern across the region. … I could no longer participate in implementing the policies to be in compliance. That’s really the only choice I had. That is what has been passed. … What I say is I didn’t just quit my job, I quit the state.”

Students are also feeling the effects of the book bans within the district. Expressing their concern, an Escambia County high school student in the district said:

“Banning those books will lessen a teenager’s world of knowledge and will constrict them of what they could learn about others and the hardships that they face.”

However, parents, authors, publishers, and advocacy organizations are fighting back by filing suit in federal court. The suit is brought by PEN America, Penguin Random House, publisher of many of the books banned by the district, authors: Ashley Hope Pérez, David Levithan, Kyle Lukoff, Sarah S. Brannen, and George M. Johnson, who have all had books banned by the district, and several parents on behalf of themselves and their respective children. The complaint alleges that the Escambia County School Board has violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments by banning books based on ideological disagreement with their content and disproportionately targeting books written by non-white and LGBTQ authors.

A federal judge has temporarily stayed the lawsuit while the court considers a motion to dismiss. Escambia County cites state statute HB 1069 as support for this motion because it grants school boards full authority over classroom materials. However, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint and emphasized that even with the passage of HB 1069 in July, the restrictions and removals that occurred prior to that date are unconstitutional.

It’s hard to determine where this case will go, but the Supreme Court has precedent with similar cases. In 1975, a parent group complained that nine books in the school library were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy.” In response, the school removed the books from its library. The case reached the Supreme Court and in 1982, the Court ruled that school libraries were places for “voluntary inquiry,” and as such, school boards could not restrict the availability of books because they simply disagreed with their content.

Schools are microcosms of society, and as such, laws that restrict what students can read and therefore learn have far-reaching consequences for more than just the classroom. The Escambia County lawsuit highlights the tensions in the United States regarding race, gender, and free expression. Access to information is important for students to become better citizens. The books being banned are important texts because students need to see themselves in the books they consume. Books can also be sources of learning empathy when students read about characters who have different experiences and worldviews. Highlighting this importance, Michelle White stated:

“I believe in what libraries do with a purpose. It’s who I am, it’s why I’ve always done what I do. And to see it all be taken away was just heartbreaking … My best phrase that I always fall back to is—books provide windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors … the ultimate goal is that when you do get to meet someone who may have a lived experience that you read about in the book—now you’ve got common ground where you can open that sliding glass door and walk through it and have a real conversation with someone (and) have true understanding and empathy, simply by reading a book.”

Suggested Citation: Deanna Palma, School Book Bans: The Fight for Students’ Right to Read, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter (October 27, 2023), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/school-book-bans-the-fight-for-students-right-to-read/.

Deanna Palma is a second-year law student at Cornell Law School. She obtained her bachelor’s degree in History and Secondary Education from SUNY Geneseo in 2018 and her master’s degree in Literacy Education B-12 from SUNY Brockport in 2019. Prior to starting law school, Deanna worked in education at the middle and high school levels.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010