Morocco’s Divisive Family Law: Harmonizing Tradition and Modernity?

September 8, 2011Student Blogs Article Morocco’s 1958 Code of Personal Status may have looked like 20th-century legislation, but it codified aspects of Shari’ah family law that had been in place for over a thousand years. Men had the right to take up to four wives, for instance, and male guardians chose most women’s—or young girls’–marriage partners for them. But in 2004, King Mohammed VI replaced the Code with the Moudawana, ushering in a new era of family law by enshrining gender equality and more expansive rights for women. My Note, forthcoming in Cornell’s International Law Journal and available at the Scholarship@Cornell Law repository, evaluates the impact of this divisive reform.

Morocco’s 1958 Code of Personal Status may have looked like 20th-century legislation, but it codified aspects of Shari’ah family law that had been in place for over a thousand years. Men had the right to take up to four wives, for instance, and male guardians chose most women’s—or young girls’–marriage partners for them. But in 2004, King Mohammed VI replaced the Code with the Moudawana, ushering in a new era of family law by enshrining gender equality and more expansive rights for women. My Note, forthcoming in Cornell’s International Law Journal and available at the Scholarship@Cornell Law repository, evaluates the impact of this divisive reform.

The Moudawana warrants attention because it is a rare example of change from traditional Islamic family law to modernized family law still based on Islamic principles. Although controversial in Morocco, the Moudawana illustrates how sacred tradition need not be inimical to modern, rights-based law. Approximately 1.5 billion people in the world practice Islam and a multitude of countries and communities continue to adhere to Shar’iah. Thus, a law like Morocco’s that reconciles traditional norms with more contemporary conceptions of rights, whether successfully or fruitlessly, has implications for a large portion of the world.

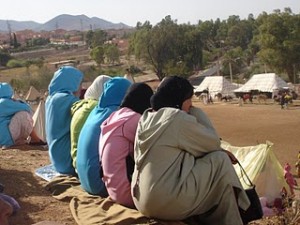

Despite significant achievements, the Moudawana still faces major policy challenges seven years after enactment. To assess what may keep Morocco’s society, judiciary, and rural communities from incorporating the new law into everyday life, I conducted field research with the financial assistance of the Kristan Peters-Hamlin Fund for Women in the Middle East. Qualitative accounts from Moroccan women combined with academic research confirmed that myriad socio-cultural factors impact the Moudawana’s practical efficacy. Judges who disagree with the law; families who use loopholes to circumvent certain provisions, such as the new minimum marriage age of 18; limited training for officials; and some women’s reluctance to exercise their new rights are a handful of phenomena illustrating the Moudawana’s limitations. Due to an intricate interplay of religion, culture, and infrastructure, the law as written has been only partially implemented.

An effective method for mitigating such tension between new laws and customary practices will inform rights-based reforms worldwide. My Note proposes that stakeholders in the Moudawana’s implementation should consider the novel, culturally-conscious approach of one Sierra Leonean NGO, “Timap [Stand Up] for Justice.” By using trained paralegals who work in their communities of origin; a philosophy that tradition is inherently malleable; and a multi-faceted method of meeting community members’ needs, Timap works to bridge the gap between “external” and engrained norms. The Moudawana and other reform movements could similarly be strengthened with an implementation mechanism that facilitates rights literacy, access to justice, community-based mediation, and grassroots advocacy.

Ann Eisenberg is in the class of 2012 at Cornell Law School, and her Note, Law on the Books vs. Law in Action: Under-Enforcement of Morocco’s 2004 Family Law Reform, the Moudawana, won the second place 2011 Cornell Law Library Prize for Exemplary Student Research.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010