Suggested Citation: Daniel Bromberg, Looks Like Lochner: will employers’ property interests consume their employees’ rights to physical and digital property access?, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter (April 11, 2023), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/looks-like-lochner-will-employers-property-interests-consume-their-employees-rights-to-physical-and-digital-property-access.

Looks Like Lochner: will employers’ property interests consume their employees’ rights to physical and digital property access?

April 12, 2023Feature . Uncategorized Article(Source)

In Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid (2021), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act (“ALRA”) constituted a per se physical taking under the 5th Amendment’s Takings Clause (applicable to states through the 14th Amendment). The ALRA gave union organizers a “right to take access” to an agricultural employer’s worksites to help employees exercise their union rights. This “right to take access” violated the Takings Clause in its infringement on a property owner’s right to exclude persons from their property.

Furthermore, the ability of union organizers to access worksites inconveniently distant from public spaces has enabled isolated workers to learn about and exercise their workplace rights. Think of workers in a ski town or at one of Orlando, Florida’s many amusement parks. There is no public property where workers can easily meet near their workplace to organize—all the surrounding land is the employer’s private property. As a result, the NLRB has interpreted the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) to permit permits non-employee union organizers to access an employer’s physical premises to organize workers. The Court in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid overturned a California law creating that right because it constituted a per se taking in violation of the Fifth Amendment. These kinds of rights, which derive power from various sources, could soon be implicated by the Takings Clause should the Court continue to expand its reach and its interpretation of property rights.

Workers also use their employer-provided workplace email to organize, especially in the post-COVID remote work era. The Supreme Court could soon come for those limited rights. How would a claim alleging a taking by the NLRA’s requirement that employers sometimes allow their employees to access workplace IT-resources for organizing look? Cedar Point identified three kinds of takings effectuated by regulatory actions: “regulations that impose permanent physical invasions, regulations that deprive an owner of all economically beneficial use of his property, and the remainder of regulatory actions.” While the first two are per se takings, the third are evaluated under the Penn Central balancing test. In these cases, courts examine three factors to decide whether the regulation at issue acquires or destroys property. Courts consider the nature of the government action, whether it “has gone beyond ‘regulation’ and effects a ‘taking’,” and if it “interferes with reasonable investment-backed expectations.”

In Cedar Point, the Court found that the regulation acted as an easement and was a per se physical taking because it appropriated a right to invade private property. The government does not have to physically seize property for its actions to constitute a physical taking. Rather, the government effects a physical taking when it infringes upon “an owner’s use” of their private in a way that amounts to a private easement.

Cases involving digital property will most likely not “deprive an owner of all economically beneficial use” of their property because digital technologies negatively scale in a way where additional users do not impose additional costs on the property owner. The NLRB recognized this reality in Purple Communications (2014). Therefore, the taking claim would likely have to constitute a permanent physical invasion or a remainder regulatory action.

Net neutrality could conceivably effectuate a permanent physical occupation of private broadband networks by essentially granting Internet content providers “a permanent virtual easement across privately owned broadband networks to deliver content to end-users,” thus depriving “broadband providers of the right to exclude others from their networks.” Professor Daniel Lyons argues that net neutrality regulation “effectively grant application and content providers unfettered access to the physical wires that comprise the network.” Lyons argues alternatively that net neutrality may constitute a regulatory taking because net neutrality, at the very least, interferes with broadband providers’ reasonable investment-backed expectations.

The Supreme Court could similarly apply these arguments to an employee’s theoretical NLRA right to use a workplace email account for organizing. However, this interpretation of the actual taken property interest is incorrect. These arguments regard the physical hardware as the primary property interest, and not the digital uses it enables. But people replace Wi-Fi modems or workplace network servers that do not boot because they are incapable of providing access to the internet or digital files—the actual, valued property interest. This digital space is not physical or intangible property. It is digital property, characterized by Moore’s Law and essentially nonexistent marginal costs per user.

The facts of Ruckelshause, a 1984 Supreme Court case, mirror claims that would appear in a suit alleging that the NLRA’s requirement that employers, in some cases, allow their employees to use workplace IT-resources for organizing: regulation requires one party to turn over data that Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) then used to evaluate subsequent candidates— a public use with some conceivable public character. Similarly, the NLRA’s purpose is public: to enforce Congress’ intended protection of the fundamental right to organize. The Court also refused to consider the constitutionality of the statute in question because the employer can seek some remedy for uncompensated takings. Under the NLRA, an employer can argue that the standard currently governing employee access to their IT-resources unreasonably abrogates property rights. If it does not, the standard likely does not “go beyond regulation” to qualify as a taking.

Regardless, any takings inquiry must still pass the threshold question of whether the Fifth Amendment recognizes the infringed property right. The term “property” in the Taking Clause “denote[s] the group of rights inhering in the citizen’s relation to the physical thing, as the right to possess, use and dispose of it.” The right to exclude is “one of the most essential” parts of this “group of rights.” The Supreme Court has stated that, in the takings context, “property interests . . . are not created by the Constitution. Rather, they are created and their dimensions are defined by existing rules or understandings that stem from an independent source such as state law.” The NLRB is an independent federal agency empowered by the NLRA, passed by Congress in 1935. Its regulations and interpretations of the NLRA are independent sources of law.

The National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”) has already recognized distinctions between digital and physical property. Other agencies like the FCC are also examining that delineation. In a previous blogpost, I discuss the NLRB’s development of case law regarding the limits of the right to exclude vested by digital property ownership. Part of that blogpost also emphasized the developing practical distinction between “physical” property and “digital” property. While the law governing digital property slowly develops, people the law seeks to regulate will continue using new technologies in novel ways. In the labor movement, social media is increasingly relied upon to create channels of communications for workers free from increasingly prevalent employer surveillance. And labor organizers are leveraging data and digital marketing to reach workers in smaller workplaces, who win their unionization campaigns at higher rates compared to larger workplaces, in a more cost-effective way than solely in-person organizing allowed for.

While the Supreme Court has not fully spoken on the distinction (but has acknowledged that some intangible property can be subject to takings), the categorization of digital platforms and tools as physical property, rather than digital property, could open the floodgates to Takings Clause litigation that restricts the rights of employees to use these tools in their organizing.

The Court has recognized intangible interests as property for the purposes of takings, including intangible property rights protected by state law.

The law’s recognition of rights granted by intellectual property ownership further exemplifies how the law contemplates different forms of property. The Supreme Court has ruled that trade secret property recognized under state law is a property right protected by the Takings Clause. The Federal Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals (the per se appellate jurisdiction for federal patent appeals) stated that although patents are “private property interests,” they are not constitutional property recognized by the Takings Clause. That point was vacated on en banc review. But the Court has distinguished between intangible and tangible rights in the past. In 1987, the Court’s McNally decision stated that a mail fraud statute was “limited in scope to the protection of property rights” and would not protect “too ethereal” interests. In doing so, the Court made the type of interest and harm the analysis’s focal point, rather than a binary distinction between tangible and intangible property rights. In other words, the analysis should center the nature of the right, as opposed to its form. At the same time, the Court implicitly recognized that tangible and intangible property vest their owners with rights of varying natures—which is often impacted by the form of the property. Perhaps either focus is effectively the same, but the adopted approach allows for more judicial discretion because property cannot be binarily labelled.

Still, the Thomas Supreme Court watered the wilting clause with Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid in 2021. Maybe influenced by its ideological shift further towards conservatism from 2016-2020, Cedar Point marked the first time in years that the Supreme Court expanded Takings Clause doctrine. Cedar Point is also the first Takings case to come from the Thomas Court. The Court’s conservative majority shows interest in advancing private rights at the expense of collective rights and has demonstrated its willingness to overturn decades-old laws that protect the right to unionize and all its associated privileges.

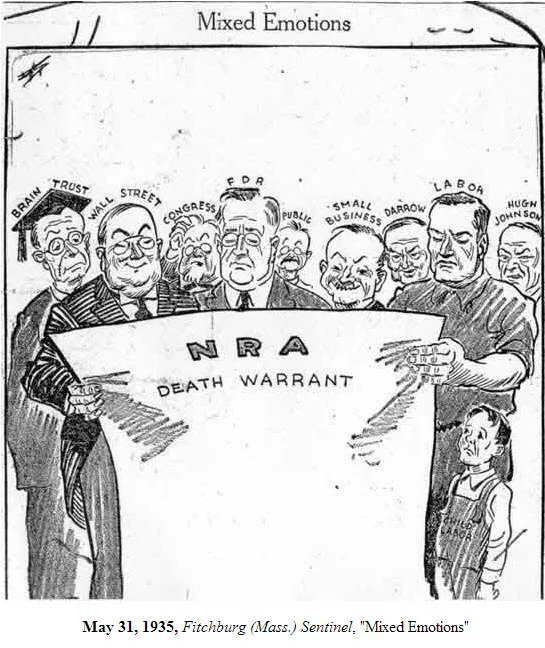

As Thomas’ Supreme Court expands Takings jurisprudence for the first time in decades, the future viability of digital organizing is at risk. This prospect is not dim. The Court has demonstrated willingness to erect legal barriers to labor organizing tactics unions have used since the 19th century, from workplace visits by organizers in Cedar Point (decided in 2021) to strikes in Glacier Northwest (the Court held oral arguments on January 10th, 2023). History has shown that the Court can and will use its power to enforce its own policy preferences. During the Lochner era, the Court overturned many economic regulations because they violated the (at the time) fundamental, constitutionally protected freedom of contract. And as agencies develop their own ways to interpret digital property, the Court may seize an opportunity to “unify” the law governing the distinction between digital and physical property in a way that decimates rights to organize based on characteristics of physical property not shared by digital property.

But the law should contemplate the uniqueness of digital property: it scales differently. It’s not like contract rights, intellectual property, or trade secrets. All those intangible properties are a limited resource. In other words, the owner’s use of their property somehow suffers because others can access it. Trade secrets are kept to ensure that only its owner can profit from the sale of the secret’s product. Similarly, a physical space can only fit so many people. But digital technologies are different because of Moore’s Law and because of no additional costs per user. One gigabyte has the data storage capacity of a pickup truck filled with books. And the price per gigabyte has steadily decreased over time. Meanwhile, the price of a house in the U.S. has fluctuational increased over time. Digital technologies have an upfront physical hardware cost for access to a seemingly infinite level of digital use that does not diminish per user.

Courts should also incorporate that understanding when considering whether, or in what unique cases, regulations of digital properties can constitute a regulatory taking. It costs an employer approximately nothing to allow its employee’s use of workplace email for organizing. The current NLRB case governing that allowance, Caesar’s Entertainment (2019), permits access in one very limited instance: when employees have no other reasonable means of communications.

Ultimately, the law should not view physical access and digital access in the same light. Digital organizing will become increasingly important if the Court continues to curtail access to physical property for union organizing purposes in favor of private property rights, like it did in Cedar Point. Glacier Northwest, the petitioner in Glacier Northwest, in its brief to the Supreme Court emphasizes this point. The brief urges further examination of Cedar Point’s recognition that the Court’s past labor law decisions failure to “afford adequate respect for employers’ property rights,” especially the right to exclude (see Right to Strike, Take a Hike! Evisceration of right to workplace speech continues.). The Cedar Point Court highlighted Babcock & Wilcox Co. (1956), one of its past decisions that permitted non-employee union organizers to distribute union literature on company-owned parking lots. In its brief, Glacier Northwest reminds the Court that it deemed Babcock “constitutionally dubious.” The Court should not take away the right to digitally organize as well. Otherwise, we’re left with a legal regime that totally favors private property over collective workplace rights.

Daniel Bromberg is a second-year J.D. candidate at Cornell Law School. He graduated with his B.S. in Industrial and Labor Relations in 2020 from the Cornell School of Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR School). In addition to being involved with the Journal of Law and Public Policy, Daniel is also a teaching assistant for Labor and Employment Law in the ILR School, the Student Representative on the Cornell Law Faculty Appointments Committee, and the Graduate and Professional Student-Elected Trustee representative on the Cornell University Board of Trustees.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010