American Infrastructure and the Biden Administration

November 18, 2021Authors . Feature . Issue Spotters . Student Blogs Article(Source)

On March 31, 2021, the White House issued a press release on the first landmark piece of legislation for the Biden administration, “The American Jobs Plan.” The Administration describes the Plan as “an investment in America” amidst a time of mounting climate change concerns and increasing inequality. The Administration also touts the Plan as a strategic component of the “Build Back Better” framework, President Biden’s proposed solution to tackle many of America’s most pressing issues in both physical and human infrastructure. To that end, the Administration is seeking to frame the Plan as a tool to combat “long-standing and persistent racial injustice.” To understand the impetus for such a claim, one must be familiar with the strong historical connection between infrastructure and racial injustice as well as the implications that improved access to quality infrastructure may have for marginalized communities.

I. How does the American Jobs Plan Address Racial Injustice?

While the American Jobs Plan seeks to improve antiquated structures across many industries, most objectives in the bill focus on infrastructure. According to the press release, “the United States of America is the wealthiest country in the world, yet we rank thirteenth when it comes to the overall quality of our infrastructure.” To correct this deficiency, the Jobs Plan allots large amounts of capital to improve highways, bridges, ports, and roads. Simultaneously, the Plan also focuses on community-level improvements that are more likely to directly impact citizens.

Primarily, the American Jobs Plan aspires to use infrastructure improvement as a means to remedy racial and socioeconomic disparities. To accomplish this goal, the Plan first calls for the redevelopment of idle properties that formerly provided industrial and energy related services. These abandoned sites, predominantly located in economically disadvantaged communities, are now “sources of blight and pollution.” Thus, this objective entails a $5 billion investment in repositioning and remediating these sites to curtail pollution and attract sustainable economic development. If executed properly, this initiative will fuel economic growth and job creation in communities that desperately need it.

While this repositioning initiative is arguably a great first step, the Plan contains more pointed solutions to tackle inequality. Specifically, the Plan calls for the rebuilding and upgrading of highways, bridges, and transit systems among other aspects of American infrastructure. The objective of this rebuilding is to “advance racial equity by providing better jobs and better transportation options to underserved communities.” To do so, the Plan must focus specifically on highways and transit systems that covertly deprive certain communities, mostly people of color, of meaningful access to these vital resources. Unfortunately, many Americans are unaware of the fact that a significant portion of their fellow citizens still rely on an antiquated transit system that is a vestige of de jure segregation. De jure segregation is the “legally allowed or enforced separation of groups of people.” Ultimately, to understand how the remnants of such segregation continues to influence socioeconomic realities today, it is necessary to engage with this facet of American legal history.

II. Why Are These Changes Needed: Historical Context & Contemporary Effects

In the days of Jim Crow, American transportation infrastructure was a bastion of the de jure segregation regime. The foundation of this regime was bolstered by several landmark legal cases including the notorious, Plessy v. Ferguson and the lesser-known case, New Orleans & Texas Railway v. Mississippi, which “permitted states to segregate public transportation facilities.” One might understandably assume that in the century of American history following these decisions, all semblance of their impact has been eradicated. But this assumption is far from the truth. Vestiges of this period linger even today influencing individual reliance on public transportation. For example, according to a notice from the American Bar Association, “African American car ownership is the lowest of any racial or ethnic group in the United States.” Though seemingly benign, this fact had real consequences in the advent of Hurricane Katrina, as many African American residents in Louisiana were simply unable to follow evacuation plans that were conditioned on car ownership. Sadly, this anecdote merely one example of the lingering effects of de jure segregation in transportation and land use law.

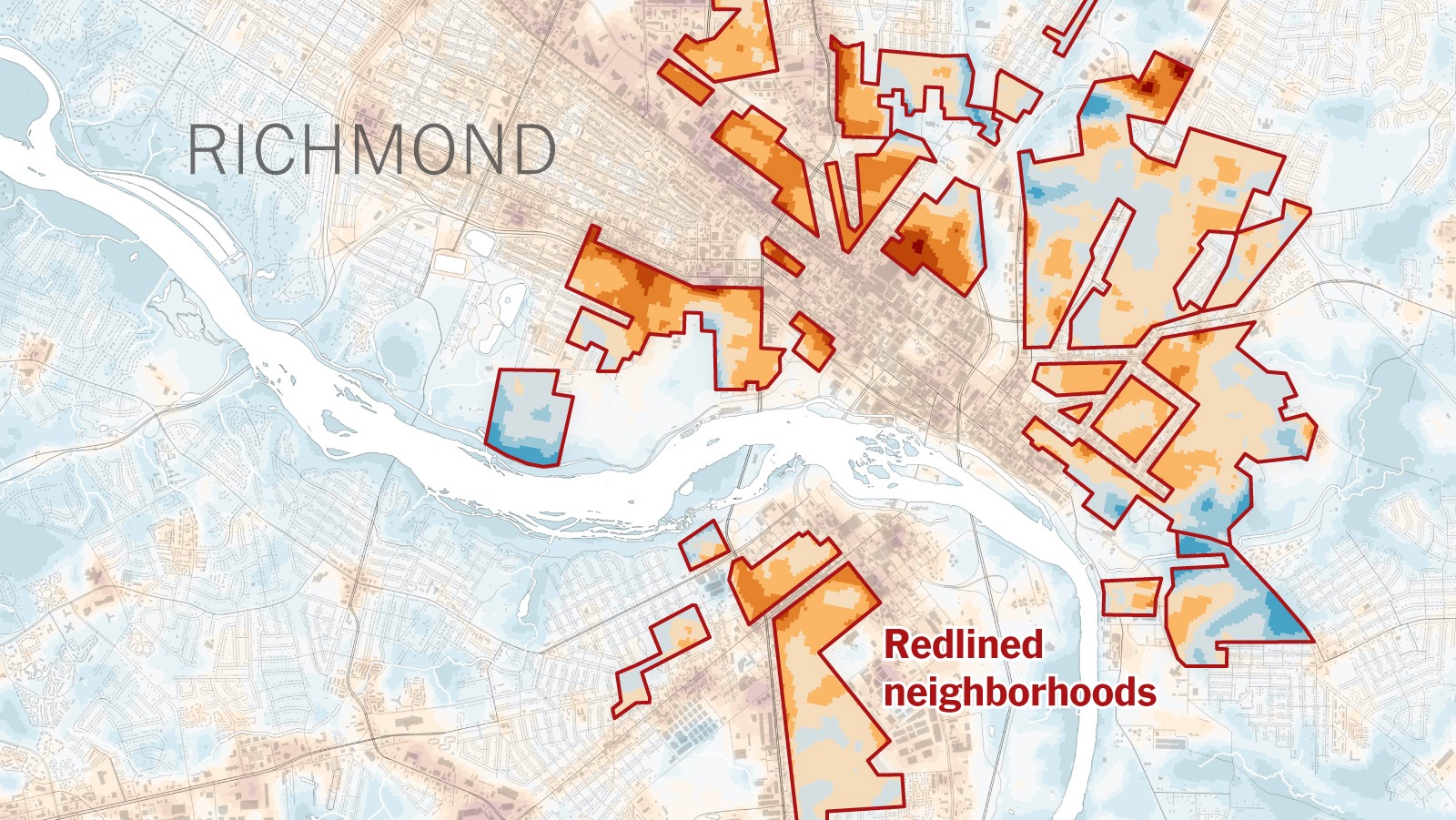

In his award winning book The Color of Law, author Richard Rothstein highlights countless examples of these exact effects. He argues that American legal history is marked by deliberate, government-sponsored de jure segregation. Rothstein’s argument is that racially motivated zoning and land use laws, which required calculated government action, divided America in the post-Civil Rights era. Specifically, following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, de jure segregation in the United States surreptitiously escaped the wholesale elimination that many idealized. While practices like “redlining” and “blockbusting” defined this era, more covert practices in zoning law have had lasting effects that continue today.

As one notable example, Rothstein asserts that American public schools are more segregated today than they were 40 years ago. In making this claim, Rothstein relies on data from the study, “For Public Schools, For Segregation Then, For Segregation Since” which shows that exposure to White students for the typical Black student in public schools was less in 2009-2010 than in 1970-1971. This is almost certainly due to racist practices in the issuance of FHA loans during the time that made buying a home at an affordable price unattainable for most people of color. Consequently, many people of color were forced to reside in multifamily apartment complexes that, due to state-sanctioned zoning practices, were generally located in poorer parts of town away from the affluent, predominantly white suburbs. Moreover, the denial of FHA loans to people of color deprived many of the opportunity to build up equity in their respective residences, robbing them of generational wealth and economic opportunity.

These calculated decisions in both zoning and transportation have had lasting socioeconomic consequences that still exist today. According to the press release accompanying the American Jobs Act, “households that take public transportation to work have twice the commute time, and households of color are twice as likely to take public transportation.” Moreover, given the “crumbling” state of American transit systems, households of color are more likely to experience transportation issues and delays. Beyond mere inconvenience, these issues essentially force residents of these communities to take employment opportunities in locations serviced by this inadequate transit infrastructure. Thus, due to the locations to which zoning committees forced minority communities, many are robbed of potentially lucrative employment opportunities that necessitate transportation by car to arrive on time or even reach the place of employment.

In addition to these economic harms, racist zoning laws have also contributed to generations of “environmental racism”, or “the disproportionate burden of environmental hazards placed on people of color.” For example, low-income and minority neighborhoods today are disproportionately impacted by the negative health effects of lead water pipes and air pollution from ports and power plants. Moreover, “African-Americans are 75 percent more likely than other Americans to live in so-called ‘fence-line communities,’ defined as areas situated near facilities that produce hazardous waste.” As a result, Black Americans today are “subjected to higher levels of air pollution than White Americans — regardless of their income level.” This is just one example of how such ill-intentioned land use plans have caused generational harms that have never been rectified. Faced with such alarming problems, the Biden administration is seeking to use the Plan as a potential remedy. Nonetheless, the question remains as to whether the Plan will be used as a political expedient that overlooks the root causes of the problem.

III. Will the Plan Be Successful?

The American Jobs Plan presents a chance for the federal government to mitigate the generational harms caused by racist infrastructure and zoning laws. As stated in an article from Northeastern University, “it’s high time the federal government began to undo the damages caused by ‘racist infrastructure’ that have helped shape economic disparities among communities of color and white communities.” Unfortunately, this progress may be much more difficult to attain than the Plan imagines. According to Joan Fitzgerald, Professor of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northwestern, even one portion of the Plan designed to reconnect highways to marginalized communities may prove problematic. The issue is that such projects will be inevitably entrusted to real estate developers whose incentives are typically misaligned with those of struggling communities.

Unfortunately, this scenario is a microcosm for the Plan at large. Legislators have already cut funding to facets like the Reconnecting Communities Initiative from a proposed $20 billion down to $1 billion. One pundit worries that even if funding for aspects such as the transit objective are kept intact, zoning laws may still prevent a critical mass of affordable housing from being built such that local governments will be able to recoup the costs of improved access. These criticisms show that the Plan may be proposing solutions that do not fully account for the complexities of implementation. Such complexities are further exacerbated by disparate goals that may evidence a lack of legislative focus. For example, a large portion of the bill’s transportation funding is allotted to tax incentives for the purchase of electric cars. While this goal is certainly laudable, it appears somewhat unrelated to addressing the “persistent racial injustice” the Plan frequently touts.

Ultimately, while there is a myriad of criticisms regarding the long-term effects of the Plan, there is still much to applaud. It is promising that as of August 10, 2021 a compromise bill of $1.2 trillion for physical infrastructure was passed in the Senate and recently signed into law. House representatives however continue to push back, demanding more focus on “human infrastructure” via budget reconciliation. While this process is still incomplete, allocations have already been cut from approximately $3.5 trillion down to $2 trillion. As a result of ongoing debate, it is uncertain what elements of the Plan will remain, but this resistance in the House is an indicator that Democrats are unwilling to concede on facets promoting racial equality.

Regardless of these partisan concerns, the bill must maintain certain critical components to have a genuine, lasting impact on inequality. For example, a top priority must be the approximately $213 billion allotted for affordable housing in order to quell concerns about the increased costs of improved transit systems. Legislators must also pay special attention to the aforementioned objectives that will combat environmental racism including improved access to clean water and the redevelopment of idle property. While compromise will ultimately be necessary to get the bill passed, legislators cannot allow funding cuts to render the Plan an ineffective tool in combatting generational inequality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is promising to see the Biden Administration engaging with the storied racial history of this country and acknowledging how vestiges of the pre-Civil Rights era continue to shape modern life. While acknowledging the interconnectedness of these issues is certainly a step in the right direction, it ultimately does very little to help American citizens on the ground. This Administration must take clear and decisive action to actually eradicate these vestiges of Jim Crow and “Build Back Better” for all citizens, not just a select few. Consequently, the American Jobs Plan may be the best opportunity for this Administration to show its commitment to curtailing inequality and increasing economic opportunity for disadvantaged communities. With bipartisan support for the human infrastructure portion of the Plan, this Bill may be able to accomplish just that.

About the Author: Brandon Richards is currently a 2nd year student in the 3-year JD/MBA program at Cornell University. Brandon graduated from Villanova University in 2020 with a Bachelor’s in Business Administration in both Economics and Real Estate. After graduation in 2023, Brandon plans to leverage this strong foundation in business and law as a corporate associate attorney in the mergers and acquisitions space. He currently serves as an online associate on the Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy.

Suggested Citation: Brandon Richards, American Infrastructure & the Biden Administration, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (November 18, 2021), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/?p=3818&preview=true&_thumbnail_id=3819.

You may also like

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010