Protecting Patents from the Looming 3D Printing Storm

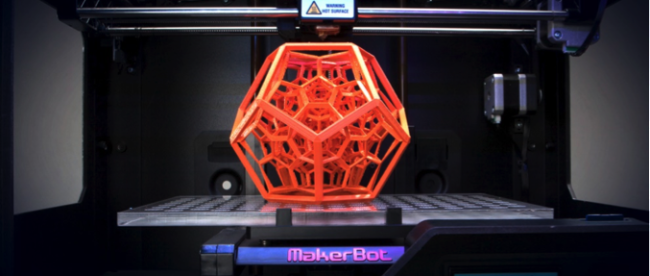

The current state of U.S. patent infringement law does not meet the challenges of 3D printing technology. 3D printing is a process in which a printer produces a physical three-dimensional object from a “CAD” file, which is an image file formatted for computers. Owners of the printer merely have to upload the CAD file onto the printer to reproduce the desired object. Although 3D printing has yet to gain broad use and appeal, the law may need to catch up with the technological advancement. Data indicate that 3D printing could be mainstream in even five years.

The federal statute controlling the area of patent infringement (including 3D printing) is 35 U.S.C. § 271. The statute explains both direct and indirect patent infringement. Direct infringement is the act of making, using, selling, offering, or importing into the U.S., any patented invention, without permission. Indirect infringement, is any act that is not direct infringement, but which requires some knowledge and intent regarding the actual infringement.

The federal statute protects against infringement in the most basic sense. In Bauer & Cie. v. O’Donnell, the Supreme Court ruled that physically reproducing a patented invention is the same as “making” a patented invention (direct infringement). 3D printing fits into the category of “making” because the process involves physically reproducing the invention layer by layer. However, if 3D printing is widespread, patent holders will face greater harm by those distributing the CAD files than those who are actually printing the patented invention. The distributors can upload and make the files available to all privately-owned 3D printers on the internet. This opens the door for actual direct infringement by a potentially enormous population.

Two recent cases shed light on how the federal statute inadequately combats patent infringement by 3D printing. In Transocean Offshore Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v. Maersk Contractors USA, Inc., the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit said that a patented invention sold along with its blueprint constitutes “selling” in the meaning of the federal statute. However, the Court did not say that sale of the blueprint alone meant “selling,” because historically, patent infringement has always involved the actual invention. Thus, even if a person sold a CAD file for a patented invention, it would not fall under direct infringement simply because the actual invention was not sold.

In Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A. the Supreme Court addressed a form of indirect infringement known as “active inducement.” Any person who actively encourages or persuades another to commit direct infringement would be an indirect infringer under the statute. The Court held that the active inducement of direct infringement occurs if the alleged inducer is “willfully blind”, in that he believes that there is a high likelihood that infringement will occur but deliberately avoids learning the truth of the matter. For example, if Alex transferred a CAD file for a patented invention to Bob, who mentioned wanting to print from the file on his 3D printer, and Alex then purposely avoided learning if Bob actually printed the invention, Alex would be acting willfully blindly and is an indirect infringer.

However, in practical terms, the willful blindness method would only prohibit the most obvious cases of indirect infringement; the subjective requirements are too difficult to prove. Could Alex be said to have known that giving the file to Bob was likely to result in patent infringement if Bob never made any mention of his desire to print from the CAD file? Additionally, if Alex and Bob stopped communicating with each other simply because they dislike each other, could it be said that Alex is also trying to avoid learning whether actual infringement occurred? Thus, unless the surrounding facts of the actual infringement are absolutely clear in showing that Alex knew that actual infringement would occur, it is far too difficult to prove indirect infringement.

Though it is clear that the federal patent infringement statute affords some protection against wrongful 3D printing, it is only effective in the simplest cases. It does not include thoughtful analysis on how new technologies are circumventing traditional modes of patent infringement. Mass infringement can easily occur when this technology becomes widespread and people can “make” patented items in the privacy of their own home. Indeed, any owner of a 3D printer could be a master counterfeiter, able to replicate a huge range of patented items, such as designer jewelry, as long as they have the CAD image file. More aggressive regulation must be implemented before that happens.

Judicial interpretation of 3D printing cases should also be more willing to recognize CAD files as the functional equivalents of actual patented inventions because they are ultimately used to reproduce the invention. It goes against common sense in an increasingly technological era to not hold digital information to the same standard as physical objects in cases such as this.

In addition, there should be movement in the legislative arena to require some rule that will afford patent holders protection at the distribution-of-CAD-files level. If legislatures require all CAD file distributors to agree that distributing prohibited files will almost certainly lead to direct infringement, the problematic subjective requirement for indirect infringement would be largely solved. The agreement would act as a sort of prerequisite before being allowed to lawfully distribute CAD files

Suggested citation: Danny Ho, Protecting Patents from the Looming 3D Printing Storm, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (Feb. 1, 2017), http://jlpp.org/blogzine/protecting-patents-from-the-looming-3d-printing-storm/.