Eyewitness Testimony Part II: Reducing the Rate of Wrongful Convictions

In Part I of this analysis, I introduced the problem of faulty eyewitness identification as it relates to false imprisonment in the United States. In particular, I provided some of the necessary legal background surrounding the issue of eyewitness credibility, citing the landmark cases of Neil v. Biggers and Manson v. Brathwaite. Part I of this series can be found here.

In Part II, I discuss some of the major empirical research that has come from the field of psychology and law regarding the credibility of eyewitnesses, and I highlight real-world examples that demonstrate these findings. In particular, I discuss how research examining eyewitness confidence may call for a second look at the Biggers factors.

According to the Supreme Court of the United States, judges and juries must evaluate eyewitness credibility based on, among other things, the time between the event and the witness’s testimony, the accuracy of the witness’s prior description of the criminal, and perhaps most importantly, the confidence of the eyewitness. Numerous mock-juror studies have shown that confidence has a “major influence” on jurors’ assessment of witness credibility. This is not particularly surprising, as individuals who seem quite sure of their identifications come across as more reliable than those who appear hesitant. When analyzed empirically, however, this common logic is not necessarily accurate.

Social scientists have researched the relative inaccuracies of “confident” witnesses for quite some time. Before the advent of DNA testing, however, many individuals viewed these studies as typical psychology mind-games or theory. As more and more prisoners are released because of DNA testing, however, more weight is given to these studies. The surprising result of many of these studies is that the correlation between confidence and accuracy is quite limited.

Why is confidence not a good predictor of accuracy? We can look at several reasons. First, whether in the context of eyewitnesses or otherwise, individuals tend to be overconfident. This phenomenon is often referred to as the “better-than-average” effect, stemming from multiple studies in which well over 50% of participants considered themselves to be better than average at things including intellectual ability, physical attractiveness, and ability to remember events.

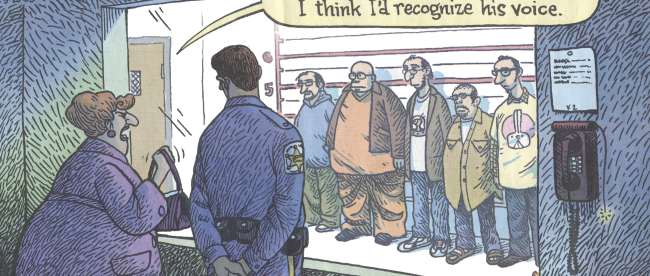

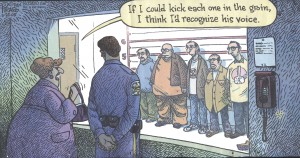

Additionally, there are a number of reasons why eyewitnesses, in particular, may be overconfident. One such reason, according to empirical research, involves feedback given by police officers or investigators. Witnesses often participate in “lineups” in which they view a group of individuals and are asked to identify the perpetrator. Imagine the impact on a witness when the investigator “confirms” the identification, stating, “That was our suspect, good job.” While many jurisdictions have taken steps to eliminate the prevalence of such “post-identification feedback,” the fact remains that such feedback can drastically alter a witness’s confidence in his or her decision.

Even without any post-identification feedback, witnesses can often be flat out wrong but remain extremely confident. A shining example comes in the story of Ronald Cotton. Mr. Cotton was convicted of rape and spent eleven years in prison before being exonerated by a DNA test. Mr. Cotton’s initial conviction came as a result of the extremely influential testimony of the victim, Jennifer Thompson. Ms. Thompson had identified Mr. Cotton in a police lineup, and the prosecution called on her to make the same identification at trial. “I was absolutely, positively, without-a-doubt certain he was the man who raped me when I got on that witness stand and testified against him,” Ms. Thompson recalls now. “And nobody was going to tell me any different.” Despite the fact that Ms. Thompson now knows Mr. Cotton was not the perpetrator and has since developed a relationship with him, she swears that Mr. Cotton is the man she saw and heard during the altercation. Ms. Thompson’s misidentification shows that confidence simply cannot be the most accurate way to measure eyewitness credibility.

So how big is the problem, anyway? While just a few hundred cases of eyewitness misidentification might be a relatively small percentage given the total number of crimes committed, eyewitness researcher Gary Wells has raised a crucial point. Wells wisely explains that we typically only know about a false imprisonment when DNA testing exonerates a convicted individual, with almost all DNA exonerations occurring in sexual assault cases. This makes sense, as DNA testing is only possible when investigators find, well, DNA. Sexual assaults generally leave traces of the perpetrator’s DNA, but murders, robberies, and other crimes may not. There is potentially a large sum of convicted murderers and thieves, for example, that may be wrongfully imprisoned with no possibility of a future DNA exoneration. These few hundred exonerations may only represent a small proportion of the total number of wrongfully-convicted individuals, indicating that the problem of faulty eyewitness identification may potentially be quite large.

I want to stress that there is not necessarily an inverse correlation between confidence and accuracy. That is to say, it is not true that all confident witnesses are usually inaccurate and unconfident witnesses are usually accurate. It is obvious that witnesses who claim to be 100% confident will likely have higher accuracy rates than witnesses who claim to be only 10% confident in their identifications. I merely stress that the correlation is not perfect, and in criminal cases with high burden-of-proof requirements with a risk of lengthy prison terms or even death, there is far too much on the line to convict someone merely because the witness seems confident.

In Part III of this series, I will discuss the other Biggers factors, citing additional empirical research that tends to suggest that the five-factor analysis laid out by the Supreme Court may need more than merely a tweak to the “confidence factor” guidelines.

It seems like the Biggers factors are extremely outdated, especially with current research. I don’t know what the Supreme Court can do to improve eyewitness testimony, however. Would they warn juries that confidence is not everything and that eyewitness testimony has proved less than accurate in multiple instances? Juries would still be affected by seeing an eyewitness testify. I wonder how much new technology in neuroscience might help in eyewitness testimony?

Social science research seems like it has played a role in changing how eyewitness identifications are viewed. All research done in this area should be scrutinized do to the sensitive nature of eyewitness identifications.