Kirk Sigmon discusses Electronic Arts’ “Origin” digital distribution platform and why digital distribution licenses for games can spell danger for customers.

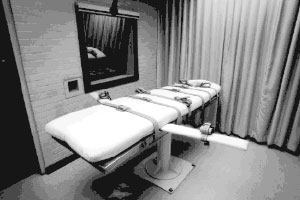

Professor Blume argues that that the resistance of those involved in the initial prosecution of defendants to admitting mistakes can be made and the suspicion of recanted testimony ultimately led to the execution of Troy Davis, even though substantial doubt was raised as to his guilt.

Can your cell phone get you 15 years in prison? In some states, if you use it to record the police, it can. Adam Kobler looks at the law behind recording the police.

Unpaid internships are a rite of passage in the film industry, but Lisa Schmidt looks at two Black Swan interns who claim those coffee runs were against the law.

Even after death, private details about the King of Pop continue to be distributed for public consumption.

Uncertainty and diminishing job prospects for undocumented youth and the pathway to permanent residency through the DREAM Act. Kemi Bello discusses.

After getting in touch with JLPP’s very first editor-in-chief, Karen Kemble, Mystyc Metrik brings you a sneak peek back in time to see how JLPP was created.

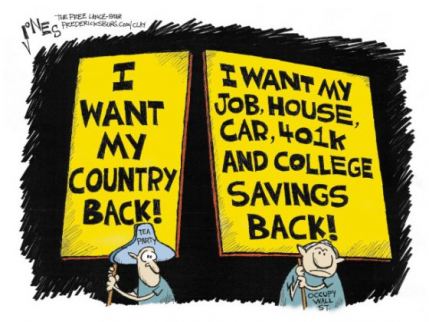

How do you wake a 200-year-old sleeping giant, the Article V Constitutional Convention? The media is abuzz with bickering between two political gangs: the members of the 53% versus members of the 99%.

The NYPD’s strategy for responding to Occupy Wall Street could be more effective at protecting the protestors’ First Amendment rights.

You’re on death row. Seven of nine original eyewitnesses have recanted. How do you avoid execution? Suzy Marinkovich digs deep into the legal doctrines that led to Troy Davis’s execution.