Exporting Miranda: How Fifth Amendment Protections Fall Flat in Overseas Interrogations

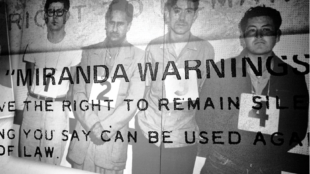

(Source) In the past twenty years, American law enforcement and the Federal Bureau of Investigation have increased their presence abroad. This increased presence is due in part to terrorist attacks against American targets and narcotics trafficking that affects U.S. citizens. Law enforcement’s role overseas is to investigate violations of American criminal laws committed by non-U.S. citizens. An integral component of the investigation process includes interrogating suspects. In the United States, any interrogated suspect is constitutionally protected by the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. However, does this same right apply to non-citizens abroad? Per circuit courts’ understanding, the Fifth Amendment still applies in offshore interrogations. What is less clear is how this right must be given effect when interrogating non-citizens. Miranda v. Arizona and its Framework Domestically, the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination protects suspects during pretrial investigations. In the landmark case Miranda v. Arizona, the Supreme Court held that prosecutors may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from the custodial interrogation of a detainee, unless the prosecution demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards. These safeguards ensure the privilege against self-incrimination. Miranda, therefore, mandates that before engaging a suspect in custodial interrogation, law enforcement officials must inform the suspect [read more]