Open, Notorious, and Continuously Occupied: A Claim for Adverse Possession

Late last summer, I received a message from one of my best friends posing a legal question: “Is it true that I can get a house for free if I squat in it?” My first year property course immediately sprung to mind—the doctrine of adverse possession is one of the most fascinating legal doctrines of the first year curriculum. But, as my friend was not a law student, I found it peculiar that she would be asking me about this relatively obscure doctrine. Her curiosity and disbelief stemmed from an ABC News special that focused on a man from Texas name Kenneth Robinson. Robinson claimed his stake in a $330,000 home for a mere $16 after the original owner abandoned the property.

To answer my friend’s question: Yes, it is true that you can claim title to property after occupying it for years. Mr. Robinson’s crafty solution of inhabiting an abandoned home and claiming its title through adverse possession—while controversial—is legal. Professor Laura Underkuffler discusses the doctrine and theoretical underpinnings of adverse possession.

A recent news media report raises interesting questions about what is “deserved,” and what isn’t, in real estate ownership. In the story, it is reported that Kenneth Robinson has claimed a “McMansion” in Flower Mound, Texas, without benefit of title. Basically, the house — which, from the photo that accompanies the article, looks to be quite upscale — was abandoned by the owner because it was in foreclosure. Robinson then came along, paid a $16 filing fee at the local courthouse, and is occupying the house under a theory of adverse possession.

A recent news media report raises interesting questions about what is “deserved,” and what isn’t, in real estate ownership. In the story, it is reported that Kenneth Robinson has claimed a “McMansion” in Flower Mound, Texas, without benefit of title. Basically, the house — which, from the photo that accompanies the article, looks to be quite upscale — was abandoned by the owner because it was in foreclosure. Robinson then came along, paid a $16 filing fee at the local courthouse, and is occupying the house under a theory of adverse possession.

Adverse possession differs from state to state, but the basic theory is this. A person who openly, notoriously, and continuously occupies the land of another may be awarded title after the requisite number of years has passed. Some states require that the would-be adverse possessor know of the illegality of his occupation. Others require that he not know of the illegality of his occupation (i.e., he is there under the color of a defective deed). But either way, the adverse possessor—if he gets that far—is awarded title for the act of occupation, alone.

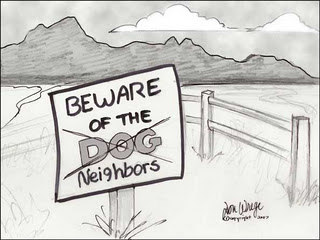

Texas is a state in which a “guilty mind” is apparently not disqualifying. Mr. Robinson is pictured leaning on an upscale countertop, the decorative stone columns of the house behind him, smiling. His neighbors, apparently, are not amused. Getting something for nothing is not the way that they achieved ownership, and they don’t believe that Mr. Robinson should either. In the words of a neighbor quoted in the story, “[i]f he [Robinson] wants the house, [he should] buy the house like anyone else had to do . . . .” A scholar in the ethics field is quoted as saying, “[w]hat may be legally permissible is not necessarily ethically right.”

Why the hostility toward Mr. Robinson, and others like him? The story cites a website, AdversePossession.com, where for $39.95, “‘average people’ can learn how to ‘acquire valuable real estate for free.'”

Ideas like the sanctity of land ownership, the work ethic, and equality are powerful in our social and legal culture, as well they should be. Because of the need for human habitation somewhere, the ownership of land is ground zero for debates over property rights. Because of the importance of the ownership of land, we cannot have ownership rules uncertain, or tenuous, or something on which the plug can be pulled by the collective or by another individual. Land ownership, once obtained through the mechanisms that the system provides, must be one of the most protected of property rights. For instance, when it comes to the taking of private property by government, we might disagree as to whether land use restrictions are something that justly trigger a compensation claim. There is no doubt about the taking of title.

Thus, the idea that land to which one has earned, legitimate, and absolute title can be lost to an entrepreneur who has simply squatted on it for the requisite number of years (five? ten? fifteen?) seems completely outrageous. It seems outrageous even if the titleholder is, as in Mr. Robinson’s case, a not-very-sympathetic character—that is, a bank which obtained title by foreclosure.

At this point, however, we must pause. Are the ethics of these cases really so simple? For instance, what if Mr. Robinson was—instead of a smiling entrepreneur, sitting relaxed at the home’s upscale bar—a homeless man, who had achieved, finally and gratefully, some kind of housing for his family?

Last year, The New York Times featured a story about an individual, Mark Guerette, who found foreclosed homes in Broward County, Florida, and leased them for low rent to needy families. The article reports that “[i]n some cases, he just mowed the lawn and replaced stolen air conditioners or broken windows; in other cases, … he let tenants make improvements in lieu of rent.” The tenants are aware of the ownership status of the houses when they move in. The article is accompanied by the picture of a tenant, Fabian Ferguson, out mowing the lawn of his new home. Mr. Ferguson and his family, who pay $289 a month in rent and were homeless before moving in, “see Mr. Guerette as a savior.” The authorities see him as a crook. As a legal blog quips, is he “Robin Hood or a fraudster?”

When we see the adverse possessor as a needy individual, who is grateful for the opportunity to live in an abandoned home, the ethical case becomes more muddled. If, after all, shelter is a critical human need, and some who occupy foreclosed homes are needy people who are in that predicament through no fault of their own, is it so certain that their occupation of such homes should be condemned on the basis of the sanctity of title and the work ethic? Isn’t this particularly true when we consider that the institutional owners of these foreclosed homes know full well that they are abandoned, and decaying, and have chosen to do nothing about it? As for the equality argument, or the idea that occupiers of foreclosed homes are getting for free what others must work for, the job of occupying and maintaining a foreclosed home—under continual threat of ouster, until years have elapsed—is not the kind of effort that most of us would consider. There is also the point that adverse possession—with its clear rules, and risks—has long been, from the days of 19th-century homesteading in the West on the land of absentee eastern speculators, an equal-opportunity doctrine.

What we find is another example of the great conundrum: law is a neutral set of rules that exist and are applied in the abstract; but to apply those rules in that way without consideration of human need, responsibility, fairness, or lack of it, propels us to aim our cannons in the wrong direction. The enemy here is not the doctrine, per se, of adverse possession. It is the inability of the law to capture the all-important human context involved in the acts of adverse possession.