Is it time to get rid of 3L?

I recently opened the quarterly interest statement for my student loans. After cringing, I began thinking about the following: should law school really be three years?

In August, President Obama endorsed a two-year program during a stop on his education affordability bus tour.

The President remarked, “This is probably controversial to say, but what the heck, I’m in my second term so I can say it. (Laughter.) I believe, for example, that law schools would probably be wise to think about being two years instead of three years — because by the third year — in the first two years young people are learning in the classroom. The third year they’d be better off clerking or practicing in a firm, even if they weren’t getting paid that much. But that step alone would reduce the cost for the student.”

President Obama continued: “Now, the question is, can law schools maintain quality and keep good professors and sustain themselves without that third year? My suspicion is, is that if they thought creatively about it, they probably could.”

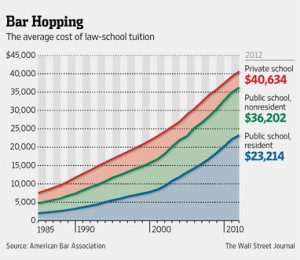

Some opponents do not believe a two-year program would lower tuition. For example, Professor Matthew Bodie of Saint Louis University School of Law argues that removing the third-year is not a fix because “law school tuition is not constrained by credit hours.” He points to the multi-decade long trend of law schools raising their baseline tuitions at rates significantly higher than inflation without a change in credit hours. Thus, Professor Bodie feels law schools would be able to justify increasing tuition under the rationale that it would be costly for schools to cram a quality legal education into two-thirds the amount of time.

Professor Bodie also thinks removing the third year will create a dilemma: “either tuition will not go down, and law schools will just make more money off their students as their costs drop, or tuition will go down, and more students will have the economic incentives and ability to go to law school. Pick your poison.”

Other obstacles and questions remain (a compilation of them is here). However, I think it is more interesting and useful to think about solutions.

The problem: the average law school indebtedness of 2012 law school graduates with debt was $108,293, while the average median starting private sector salary was $76,125.

Here is my idea. Law schools should monetize the students for the benefit of the students. Instead of bludgeoning the case method to death during the second and third years, law schools should transform into practicing law firms. First, the professors will be the partners, and the students will be the associates. Next, the law schools will then capture business through an offer of greatly reduced billing rates. Instead of writing fake briefs, student associates will work on projects that have true impact. The projects will provide students with real world experience, and professors will use their expertise to create valuable law school graduates.

It is just an idea. What do you think?