Can Texas Deny Birth Certificates to Immigrant Children

By Katherine DeVries

Texas may continue to deny birth certificates to children born in the U.S. to illegal immigrants.

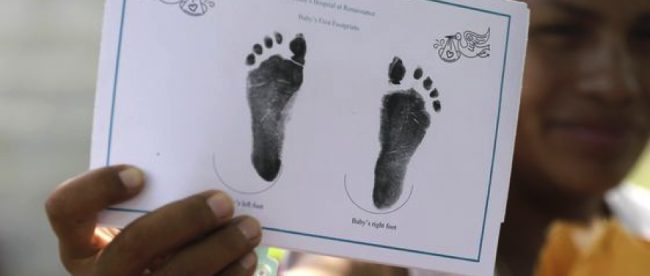

On October 16, 2015, a Texas federal judge denied an Emergency Application for Temporary Injunction that would have forced Texas hospitals to issue birth certificates to children born in the U.S. to foreign parents, pending a decision in the federal case addressing this same issue. The case was filed in June 2015 by Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, Texas Civil Rights Project, and South Texas Civil Rights Project on behalf of seventeen undocumented mothers and their children suing the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The complaint alleges that the seventeen mothers are all citizens of Mexico, Guatemala, or Honduras residing illegally in Texas. The mothers gave birth to their children in Texas and requested official copies of their children’s birth certificates from the Department of State Health Services Vital Statistics Unit, the state agency charged with the responsibility “to collect, protect and provide access to vital records and vital records data to improve the health and well-being in Texas.” The Vital Statistics Unit requires identification from parents seeking copies of their children’s birth certificates, but refuses to accept as identification foreign passports lacking U.S. visas or matrículas. (Matrículas are identity cards that Mexican consulates issue to Mexican citizens who reside outside Mexico.) Matrículas or foreign passports without U.S. visas are often an undocumented individual’s only form of official identification for a variety of reasons: confiscation of other forms of identification by coyotes (smugglers) during the journey to the U.S. or by Border Patrol at the Southern Border, expiration of or ineligibility for voting cards, loss or theft.

Thus, without an acceptable form of identification, undocumented parents are unable to obtain copies of their children’s birth certificates. “(W)ithout birth certificates, (children of undocumented parents) could easily be excluded from the benefits of citizenship due to all born in this great state,” says Rebecca L. Robertson, Legal & Policy Director of the ACLU of Texas. These “benefits” include: obtaining child care, enrolling in school, travelling across borders, and proving a parental relationship. The seventeen undocumented mothers allege that without an official copy of their children’s birth certificates they are unable to enroll their children in school, Head Start, or daycare; renew their children’s Medicaid benefits; travel; baptize their children; or access an array of other social welfare programs afforded to them, such as SSI (Supplemental Security Income). Further, proving a parental relationship without a birth certificate becomes “difficult if not impossible.”

The scope of this practice likely extends beyond the seventeen families involved in the suit. With an estimated 1.7 million undocumented immigrants in Texas, the seventeen families likely represent just the tip of the iceberg. “There are many more families out there that haven’t gotten birth certificates for their children,” said Jennifer Harbury, an attorney with the legal aid agency and human rights activist. The complaint alleges that “hundreds, and possibly thousands, of parents from Mexico and Central America have recently been denied birth certificates for their Texas-born children.”

The issue before the court is not whether the U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants are in fact U.S. citizens. The 14th Amendment clearly establishes birthright citizenship: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” However, in the wave of recent political debates surrounding immigration, the Constitutional principle of birthright citizenship creates policy questions about what to do with families that contain both children who are Americans and parents who lack authorization to live in the United States. Moreover, outside the courts, the very principle of birthright citizenship is being reevaluated.

The U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants are often referred to as “anchor babies.” Although no official definition of the phrase exists, “anchor baby” is widely understood to refer to “a child born to a noncitizen mother in a country that grants automatic citizenship to children born on its soil, especially such a child born to parents seeking to secure eventual citizenship for themselves and often other members of their family.” Not surprisingly, some consider the phrase offensive because of the term’s dehumanizing implication of instrumentality, implying that undocumented women have children for their own selfish goals of citizenship, while citizens have children for non self-serving grounds. Notwithstanding the term’s controversy, presidential hopefuls Jeb Bush and Donald Trump have used the phrase. It should be noted that the immigration policies proposed by the two candidates to address the phenomenon of U.S.-born children to undocumented mothers were vastly different. While Trump called for an end to birthright citizenship entirely, Bush proposed stronger immigration enforcement to prevent women from coming the U.S. for the purpose of having their babies.

On the other end of the spectrum, Human Rights Watch claims that both international human rights treaties and also U.S. domestic case law affirm an international human right to family unity. In response, Human Rights Watch calls on Congress to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to restore hearings to weigh an immigrant’s connections to the U.S., especially their family relationships, in deciding whether someone should be deported.

The policy implications on revoking birthright citizenship or tightening or loosening immigration law are enormous given the vast number of families in the U.S. containing both citizens and noncitizens. The House of Representatives estimates that each year between 350,000 and 400,000 children are born to undocumented parents in the U.S.; this accounts for one out of every ten births nationwide. A 2006 survey revealed that 22% of documented immigrants deported by ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) were parents of U.S. citizens. Beyond discrediting the notion that a U.S.-born child can serve as an “anchor” to prevent deportation, this statistic also raises the question of, what happens to the children when their undocumented parents are deported? Separating children from their parents often has adverse effect on the child’s mental health. Furthermore, older siblings often must step in to care for younger children when a parent is deported, limiting their own opportunities to succeed.

The debate over the phrase “anchor babies” and the pending case in Texas both call attention to the contentious public climate surrounding U.S. immigration policy. Furthermore, both highlight the impact immigration policies have, not just on individuals, but on entire families. The future of immigration policy is particularly unclear because it is not an issue that divides cleanly on party lines. What is clear is that millions of families stand to be affected by the future holding in Texas and any changes to current immigration law.