Impropriety of the Reid Technique on Developing Brains

(Source)

- What is the Reid Technique?

Custodial police interrogations have long walked the line of legality in terms of just how far officers are allowed to go to obtain a confession. Throughout the last several decades, laws have been established prohibiting physical force, denial of counsel, and other blatantly coercive tactics from being used. However, police are still able to use extremely manipulative techniques during interrogation, so long as they do not reach the extent that the suspect’s will has been overborne. The vagueness of this standard has allowed for one of the most presently controversial interrogation methods to persist over time, the Reid Technique of Interrogation. The Reid Technique has been the most popular interrogation technique since the 1960s, and is best known for the classic police officer “I’m trying to help you out” trope, but expands far beyond that. Its purpose is to elicit a confession, not discern the truth, which is contrary to the goal of the United States justice system. The interrogation itself involves nine steps to obtaining a confession, and is extremely effective, with 95% of trained officers stating that it increased their confession rates. The nine steps ultimately boil down to a method of ignoring a suspects denials, presenting false evidence against the suspect, implying that consequences will be lessened if the suspect is helpful, framing the suspect’s conduct as minimally consequential, offering false alternatives as to how events occurred, and overtly assuming the suspect’s guilt. The combination of these tactics is so manipulative that the technique has become known for resulting in false confessions. It is difficult enough for an adult to hold up to this kind of psychological pressure, let alone children, yet in many cases, utilizing Reid Technique tactics on juvenile suspects has been permitted.

2. Why the Reid Technique is Inappropriate for Use on Juveniles

Psychological implications

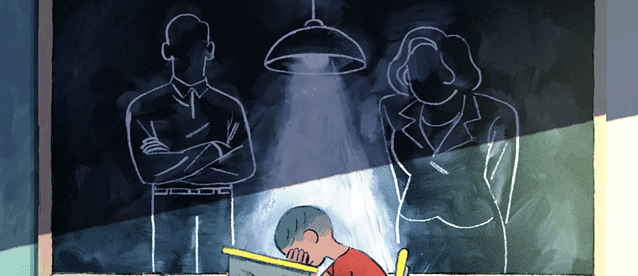

While Reid Technique deception is controversial in all cases, it is particularly problematic when used against juvenile suspects because of the psychological susceptibility of their developing brains. Teenagers and children have less sophisticated reasoning abilities and are more susceptible to social influence. Specifically, the risk-assessment portion of the brain does not develop until the mid-twenties, so teenagers and children tend to focus more on the immediate rather than the long-term, making them likely to confess just to get out of the uncomfortable interrogation, without fully considering the long-term consequences of confessing. The Reid Manual itself warns officers to be extremely careful and to modify tactics when using this technique on juveniles because of the ease of manipulating them.

Consequently, the Reid tactics of presenting false evidence, providing irrelevant moral justifications, and refusing to acknowledge denials create a much higher likelihood of eliciting a confession with juveniles, whether or not they committed the crimes.

The Technique’s problematic use

Despite warnings against it and evidence of its dangers, the Reid technique is frequently used on juveniles just the same as adults. Two prominent cases from the last decade provide examples of how the Reid technique has been used problematically against juveniles. In In Re Elias V., in 2012, detectives pulled a 13-year old boy out of class and interrogated him in the school counselor’s office. The detectives stated as fact that he had been inappropriately touching his friend’s little sister, based solely on one 10-minute interview with a 3-year-old. The boy repeatedly denied the alleged conduct and the interrogators repeatedly ignored his denials. The officers asked specific details about the alleged offense as if there was no doubt about its occurrence. They presented false evidence by stating that the child’s mother saw the conduct occur. They told the boy a lie detector would prove he was being deceptive. Eventually the officers used maximization/minimization to offer him a less morally culpable confession by asking if he touched her because he was attracted children or just touched her for a second because he was curious. At this point, the boy “confessed” to the officers’ suggested alternative. As a result of his confession, the court declared him a ward of the state and placed him on probation in his parents’ home. In 2015, after the boy had already been subject to years of legal consequences, the court decided that the boy’s age rendered him “most susceptible to influence” and that the interrogators’ employment of techniques derived from Reid were to psychologically persuasive for use on a boy of his age. This case is not unique, and several others like it have been litigated in the past decade.

Another 2012 case, Commonwealth. v. Bell, had an almost identical fact pattern regarding the interrogation. The police pulled a 13-year-old boy out of class and interrogated him at school, stating matter-of-factly that he had had nonconsensual intercourse with his younger cousin in the shower. The police again feigned superior knowledge by telling the boy that they know everything that happened and know that his cousin did not lie to them at all. The boy repeatedly denied the allegations and the officers repeatedly ignored his denials, continuing to ask questions about specific details of the alleged act. The police also implied that he could go home if he just “told the truth.” This interrogation ended the same way as the other, with the police offering a false choice, one with minimized moral culpability, the other maximizing the wrongness of the conduct. When faced with the choice between intentionally trying to harm his cousin and just messing around and being curious, the boy admitted to the second version of events. It again took the court 2 years to dismiss the case on grounds that the interrogation was too psychologically coercive for a young teenager to produce a reliable confession. At this point the boy’s reputation and psyche were already tarnished.

Even though in these cases the Court ultimately decided that the Reid or Reid adjacent tactics employed were inappropriate when used against the juveniles involved, police have not ceased using this technique in juvenile interrogations. Even if in many of these instances courts will inevitably follow public sentiment and decide that the confessions obtained from juveniles using this technique are inadmissible, the juveniles involved will still be put through lengthy, embarrassing court proceedings and legal consequences, hoping that their case gets thrown out. This would negatively impact all parties involved because the victim of the alleged crime would not get the justice they are after, and the defendant who did not commit the crime would be dragged through the legal system. These problems are entirely avoidable if police choose to not use age-inappropriate interrogation techniques in the first place.

What can be done about it?

Opponents of the Reid Technique’s use in juvenile interrogation have begun to advocate for the use of an interrogation style frequently used in England, the PEACE method. This method does not involve a presumption of guilt, but instead begins with a plan for how the particular interview fits into the overall interrogation, what the objective is, and what topics need to be covered. The method also involves explaining to the person being interviewed how the interview works, then allows that person to tell his or her version of events without interruption before asking questions and requesting further information to explain evidentiary inconsistencies. Interviews using this method end with the police recounting what the interviewee has stated back to them, allowing for the interviewee to clarify parts of the narrative. This method would be much fairer to children because they often need instruction in order to fully understand expectations and consequences, and because they tend to defer to authority figures and are timid to correct them. This method resolves those issues in addition to not being inherently designed to be deceptive or coerce a confession out of any interviewee.

Another potential solution to decrease the potential for coercing kids into confessions is to have a stricter “interested adult” rule. Many jurisdictions do not have a rule that a juvenile is required to consult with an interested adult in order for their custodial statements to be considered voluntary. An interested adult is someone over the age of majority that is “informed of the juvenile’s rights and interested in the juvenile’s welfare,” such as a parent, guardian, older sibling, attorney, guardian at litem, etc. Because children are psychologically more susceptible to coercion than adults, to eliminate this risk, states could make it a requirement that all juveniles must have an interested adult present during an interrogation. This way the adult can intervene and explain things to the juvenile if the juvenile is having trouble understanding something or if the officer misstates something the juvenile may be too timid to correct. As for the states that do already have this requirement, there should be a higher standard for who can be considered an interested adult, to assure that the adult will assist the juvenile during the interrogation if needed, rather than just be present.

Whether it be banning the use of the Reid technique against juveniles altogether or requiring that an interested adult is an active part of the interview, a policy change needs to be made to reduce the risk of manipulated juvenile confessions. Studies show that juveniles are two to three times more likely to falsely confess than adults. They are psychologically different than adults so need to be treated different in the interrogation room. Safeguarding children’s rights depends on it.

Emily Lambert is a J.D. candidate for the class of 2024 at Cornell Law School. Prior to attending Cornell, she worked in children’s mental health as a behavioral interventionist in Vermont. She completed her B.S. in International Business and B.A. in Spanish at Norwich University. Emily is a member of the Cornell Christian Legal Society and Women’s Law Coalition, participates in Moot Court, and currently conducts non-jury trials as an intern for the Ithaca city prosecutor. Her academic interests include healthcare law and general litigation.

Suggested Citation: Emily Lambert, Impropriety of the Reid Technique on Developing Brains, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter (Nov. 23, 2022), http://jlpp.org/blogzine/impropriety-of-the-reid-technique-on-developing-brains/.